BASIC KNOWLEDGE The flyback diode explained

Related Vendors

When an inductor and switch are present in a circuit, turning off the switch can be challenging. The inductor, wanting to maintain its magnetic field, does not let go of the switch. It releases a "sparkling voltage kick" to prevent the ultimate break up. Here comes the deal-breaker - Flyback diodes. Flyback diodes combat such unwanted inductor responses through their smart connection. The article details Flyback diodes and their operation in modern electronics.

What are Flyback diodes?

During his prime time, Nikola Tesla encountered inductor-related sudden voltage spikes. However, no Flyback diodes were present by then. Using such protective circuits to reduce voltage spikes dates back to the early 1930s. In the modern age, these diodes behave like protective gear in various applications.

Definition Flyback diodes

Flyback diodes are protective components connected across inductors to eliminate sudden voltage spikes during the switch-off mode. When turned off, most devices and circuits cannot withstand such large voltage spikes, which may lead to a spark or potentially fire. Flyback diodes operate to prevent a suddenly induced voltage to “Flyback” to the power source (switch-battery).

Flyback diode symbol

The standard diode symbol represents flyback diodes. They are parallel connected with an inductor and a resistor in a circuit.

How do Flyback diodes work?

Flyback diodes mostly operate in circuits that contain inductors. These diodes operate during switch-off (open-switch) but remain inoperable during switch-on (closed switch). When the power supply is abruptly removed from a circuit, the magnetic field of the inductor collapses.

As a natural response, the inductor fights back the action by generating a voltage pulse of reverse polarity across the switch contact. This large voltage induces an electric arc, further damaging the switch contacts. A Flyback diode is connected across the inductor to divert current flow towards itself.

A Flyback diode functions like a catalyst that enhances a chemical reaction but does not take part in it— meaning— the Flyback diode does not change the original operation of the circuit. It is present only to combat sudden voltage spikes. The following section details the Flyback diode operation with an explanatory diagram.

Life without Flyback diodes

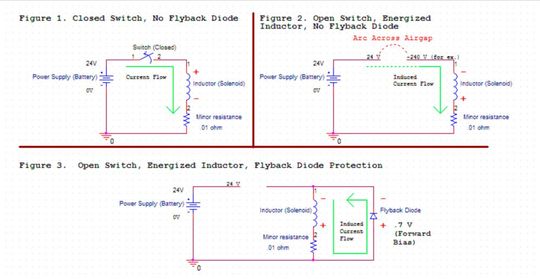

Figure 1 shows a 24 V battery connected to a series combination of an inductor and a resistor. When the switch is closed, the power supply remains on. The current from the battery flows through the circuit, flowing down the inductor. The direction of conventional current always starts from the battery's positive terminal and moves towards the negative terminal (current direction– positive to negative).

According to Faraday’s laws of electromagnetic induction, a back emf (electromotive force) is generated across the inductor- opposing the change in current flow. The magnitude of this back emf depends upon the rate of current change across the inductor. Most of the battery voltage drops across the inductor rather than the resistor. As a result, current flow slowly increases in the circuit.

The voltage drop across the resistor gradually increases more than the drop across the inductor. At some point in time, known as steady state, current flow stops increasing further as the inductor no longer generates the back emf. Eventually, the magnetic field becomes stable with negligible voltage drops across the inductor. In simple words, the inductor becomes “saturated” to behave like a wire (short circuit).

Inductive kick

Figure 2 showcases the open-switch condition in the same circuit. When the switch is turned off, the magnetic field of the inductor collapses. The inductor resists the change in current flow by generating a large opposite-polarity voltage, much larger than the battery voltage. This phenomenon is known as inductive kick.

A rule known as Lenz's law states the polarity of this newly induced voltage must be opposite to the supply voltage. As mentioned above, the conventional current produced by the supply voltage flows from the positive to the negative battery terminal. It makes the newly induced voltage positive at the lower side and negative at the upper side of the inductor. Figure 2 confirms the opposite polarity of the induced voltage.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5f/fe/5ffedb2e0ffa6/listing.jpg)

The large opposite-polarity voltage appears between the switch contacts of the circuit, ionizing air molecules between them. The electrons jump the air gap between the contacts, forming an electric arc. The electric arc allows current flow through the switch, even though the switch remains off.

The electric arc continues to burn until the inductor's magnetic field dissipates as heat. Inductors with larger inductances tend to produce intense arcs. The formation of an electric arc is an unwanted phenomenon that damages metals and burns the circuit material. In some rare cases, an arc may give rise to a fire.

The Flyback rescue

Figure 3 shows a Flyback diode parallel-connected across the network of a series-connected inductor and resistor. The Flyback diode remains off when the switch remains on (closed switch condition). This is because the battery turns off the Flyback diode through the reverse bias connection.

When the switch is turned off, the battery turns on the Flyback diode through the forward-bias connection. The Flyback diode starts to conduct. The inductor and the Flyback diode form a network in which the inductor does not generate a large voltage.

The inductor does not oppose any change in current because the Flyback diode does not let it fall to zero. Forward voltage drop of Flyback diodes limits the voltage development across the inductor to 0.7-1.5 V (for silicon-based semiconductors).

The Flyback diode provides an alternate current path to the inductor. The current flowing through this path is known as the Flyback current. The Flyback current doesn’t ”fly back” to the power source (battery) or switch contacts. It reduces to zero in a few microseconds, turning the network completely off.

Flyback diode types

Flyback diodes are simple diodes— their construction is not different from mainstream diodes. The circuit connection and operation make them Flyback diodes rather than special constructions or complex semiconductor manufacturing processes.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ff/22/ff22163c256104c22639a24e8af3565b/0113258006.jpeg)

TYPES OF DIODES - OVERVIEW

The different diode types explained

PN junction diode as Flyback diode

A standard PN junction diode is most commonly used as a Flyback diode.

Zener diode as Flyback diode

A zener diode can also function like a Flyback diode. In addition to Flyback action, a zener diode offers zener voltage regulation.

PN-Zener Flyback series

In some cases, a Flyback diode (PN junction diode) is connected in series with a Zener diode. The arrangement offers switching protection and enhances relay performance.

Flyback diode advantages

- Flyback diodes stabilize circuits.

- Flyback diodes eliminate the arc generation to protect solid-state switches.

- Flyback diodes improve component lifespan (mostly switches).

- Flyback diodes reduce EMI (electromagnetic interference).

- Common diodes like the standard PN junction diodes and Zener diodes can function as Flyback diodes, eliminating complex design procedures.

- Flyback diodes are cheaper and easier to install.

Flyback diode limitations

- Flyback diodes increase power loss.

- The current flowing through Flyback diodes in open-switch mode causes a delay in the control relay response. Simply put, they slow down the switching capabilities of a relay.

- Flyback diodes reduce armature velocity— they may weld switch contacts together, damaging the performance.

Flyback diode applications

Due to their use in various applications, Flyback diodes are also known as flywheel diodes, snubber diodes, freewheeling diodes, suppressor diodes, commutating diodes, or clamp diodes.

Flyback diodes are used in applications such as:

- Snubber circuits to dampen oscillations.

- Protective gear in inductive loads.

- Switching power supplies, solid-state switches, semiconductor switches, battery-powered systems, and automotive switches.

- Relay coils.

- Solenoid valves.

- DC-powered equipment including DC motors.

- Inverters.

References

(ID:50308481)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/71/fd/71fdcc22d9a9bd2f42985f692c4aefa2/0128924236v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/94/54/94548eaecd020681e558d563bc48ba1d/0128926221v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/29/99/2999bb9af245dd31f4c837c1d9359046/0128923137v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/10/78/107856328ef320cc081bf88e0baf95e8/0128685487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/67/62/676279913d77e1db48eb5cbe9be4c767/0128937895v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0f/a2/0fa2b5bdc21e408fd73e637d226d5210/0128681532v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4f/6f/4f6faf0ca6f748a2967d6b5bba7c88e1/0128682406v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ad/52/ad52f7b5542eff15ba54ec354d31b50d/0128681536v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/1e/9c/1e9c45d6fcf2fb48dc47756e4cb20174/0128931043v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/8b/42/8b4271e1bedea432ab03c83959e30431/0128818204v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/87/5a/875a8fa395c1eec9677e075fae7f5e8e/0128793884v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/93/2f9364112e8c6ff38c26f9ba34d0f692/0128791306v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/30/cb30ebdca7fcaea281749cb396654eb3/0124716339v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0b/b4/0bb4cdfa862043eac04c6a195e59b3e0/0124131782v2.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/60/7e/607ec89d5d9b5/white-frame.jpg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/62/a0/62a0a0de7d56a/aic-europe-logo.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/d9/64/d964e7b776e5905b69d15374f8b8990b/0115795833.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/90/f4/90f487e51d95ee8cf074826c96b8f6e5/0124400898v2.jpeg)