SEMICONDUCTOR Semiconductor materials: A comprehensive overview

Related Vendors

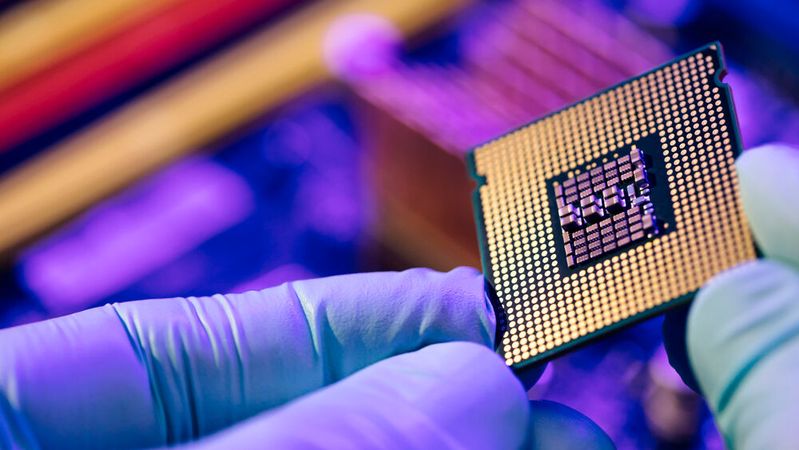

Microchips are the backbone of our digitised world. These highly complex electronic devices are constructed using a variety of semiconductor materials. As our need for computing power increases, the development of more powerful and versatile semiconductor materials has become more important than ever.

We live in a digital age. Most people are surrounded by a myriad of technological devices for every second of every day. We are now so dependent on technology that the progression of human civilisation seems inextricably anchored to the continuous development of faster, more powerful computers.

Microchips lie at the very centre of the hyper-digitalised world. As a result, the control of semiconductor production has become a major geopolitical issue. The materials used to construct semiconductor chips are now strategically important resources whose supply, processing, and technological mastery have global significance.

Worldwide semiconductor sales reached a value of US$64.9 billion in August of 2025, a 21.7% increase from the previous year. According to recent reports, the worldwide semiconductor market is projected to be worth US$1 trillion by 2030. The associated semiconductor materials market is estimated to be worth US$72.03 billion at the time of writing and is projected to reach over US$96 billion by 2032.

In this article, we explore the properties of the most common semiconductor materials and look at what materials may be used in the next generation of microchips.

Understanding the Basics of Semiconductor Materials

A microchip is a small electronic device that contains integrated circuits built on a base of semiconductor material. What makes semiconductor materials so unique is their ability to act as both conductors and insulators to control the flow of electric current.

There are two main types of semiconductor materials used to develop computer chips:

Intrinsic semiconductors: These are pure materials with no added impurities. Intrinsic semiconductors have an equal number of electrons and holes. They also have limited free electrons at room temperature, which gives them low conductivity. As the temperature increases, so does the conductivity of the material.

The limited conductivity of intrinsic semiconductor materials means that they are rarely used alone in microchips. Intrinsic semiconductor materials are usually used as the base of a microchip.

Extrinsic semiconductors: Intrinsic semiconductors are materials that have had a small number of controlled impurities added. Known as ‘doping’, this process changes the electrical properties of the material and increases the conductivity. The impurities used are known as N-types and P-types. N-type semiconductors are made by adding atoms with extra

electrons. This gives the material more negative charge carriers (electrons). P-type semiconductors are made by adding atoms with fewer electrons. This creates “holes” that act as positive charge carriers.

The transistors, diodes, and logic circuits in microchips are built from extrinsic semiconductors with P-type and N-type regions.

The minimum amount of energy required to excite an electron away from an atom (known as the valence band) to a space where they can move freely and conduct electricity (the conduction band) is known as the bandgap.

A material with a small bandgap can switch on and off easily, but cannot handle high voltages or high temperatures.

Wide bandgap materials can tolerate higher temperatures and higher voltage levels and are able to switch much faster.

Small bandgap materials are used for normal chips, such as memory chips or CPUs, while wide bandgap materials are used for high-speed chips like those in electric vehicles or 5G smartphones.

As well as the overall cost and manufacturability of the material, choosing the right semiconductor material requires comparing properties such as:

- Electron mobility

- Thermal conductivity

- Breakdown voltage

- Bandgap energy

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/67/a9/67a9bfa6e215f2657331765672a43be5/86165585.jpeg)

BASIC KNOWLEDGE - SEMICONDUCTORS

What you need to know about power semiconductors

The Major Semiconductor Materials

The three materials traditionally used to build the majority of microchips are silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), and gallium arsenide (GaAs). Si, Ge, and GaAs are used in integrated circuits such as CPUs, memory, and radio frequency integrated circuits (RF ICs).

While it is not widely used to build mainstream microchips, gallium nitride (GaN) is an important semiconductor material. GaN is now frequently used instead of GaAs for power electronics and high-frequency electronics.

Then we have silicon carbide (SiC). From its humble beginnings as an abrasive, SiC is now regarded as a viable alternative to silicon-based semiconductor chips.

It’s no exaggeration to say that these materials have provided the foundation for the development and continued advancement of modern technology.

Silicon (Si)

When looking at the hierarchy of semiconductor materials, the undisputed champion has to be silicon (Si). Used as a base for integrated circuits, Si has been integral to the development of the electronics industry for over 70 years. Almost all microprocessors, memory chips, sensors, and electronic devices contain Si. It’s so important to the digital age that a hub of technological development is named after it, Silicon Valley.

Despite its importance, this key semiconductor material is neither rare nor particularly difficult to extract. Si is found in 28.3% of the Earth's crust. It is the second most abundant element in the world and the eighth most abundant element in the universe.

While Si is relatively easy to extract, processing it into a usable form can be complex and expensive. Currently, China produces most of the world’s commercial-grade silicon. The United States, Germany, Norway, Malaysia, and South Korea are also major producers.

Classified as a metalloid, Si has both metal and nonmetal properties. It has a high thermal conductivity and has four valence electrons. It can form compounds with many other elements, making it relatively simple to dope silicon to enhance its properties.

Officially discovered in 1824 by the Swedish chemist Jons Jacob Berzelius, Si has been produced on a commercial scale since 1895. However, it has a much longer history. The ancient Chinese and Egyptians were fond of using Si in the form of silica for glass objects and ornamental jewellery.

The first ever device with a Si semiconductor was a silicon radio crystal detector invented in 1906 by an American engineer called Greenleaf Whittier Packard. In 1954, the silicon-based transistor was developed in Bell Labs by a team led by the chemist Morris Tannenboaunm. However, it was Texas Instruments that went into full-scale commercial production later that year.

Si has a bandgap of 1.12 eV (indirect), which makes it ideal for logic and general electronics but limits high-temperature performance. Si naturally forms a high-quality SiO2 oxide layer, which is crucial for building MOSFETs (Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors). Somewhere around 13 sextillion MOSFETs were made in the period between 1960 and 2018.

Its excellent mechanical strength makes it possible to manufacture large, thin Si wafers that can withstand the rigors of semiconductor processing. Si can be patterned down to the nanometre scale. Plus, it’s abundant, reliable, and low-cost. Decades of manufacturing Si for electronic devices mean that there are literally thousands of extensive design libraries available. When it comes to scalability, versatility, and cost, Si simply can’t be beat.

But that’s not to say the material doesn’t have its shortcomings. Si’s physical properties impose constraints that mean it is quickly becoming unsuitable for a range of applications.

Si’s electric field breakdown strength is relatively modest (~0.3 MV/cm). This puts a limit on how thin silicon-based devices can be before they break down under high voltages. Anything beyond 600–900 volts, and a Si power device starts to struggle.

Heat also limits its use. High-powered Si devices heat up faster and require large, complex cooling systems.

Lastly, Si transistors are approaching the atomic scale (2–3 nm). For most of the digital age, Si has driven Moore’s Law. But as Si‑based transistors now approach atomic‑scale dimensions, issues such as quantum tunnelling and leakage are severely limiting their use.

As demand for faster, smaller, and more efficient electronics increases, the need for materials that can overcome Si’s inherent physical limitations is becoming urgent. Si’s long reign as the dominant semiconductor material may be drawing to a close.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/bb/ee/bbeee2fe59ae49e462b6fd37e210da73/0123364832v2.jpeg)

SILICON CARBIDE

Lowering SiC costs: Thin wafers, strong substrates

Gallium Arsenide (GaAs)

The next major player in modern semiconductor materials is gallium arsenide (GaAs). Although its high cost and brittle structure make it less desirable than Si, GaAs still sits proudly in second place on the semiconductor material hierarchy.

GaAs is not a pure compound. As the name suggests, it’s composed of gallium and arsenic and known as a III-V compound. Just like silicon, GaAs is used as a substrate for semiconductor chips. GaAs semiconductors are more heat-resistant than silicon-based semiconductors and are also much quieter when in operation.

Compared to silicon, GaAs has much higher electron mobility and higher saturated electron velocity. Gallium has three free electrons, and arsenic has five. This supports very high switching speeds and high-frequency operation. GaAs also has a direct bandgap (~1.42 eV at 300 K), which allows electrons to directly recombine with holes and emit photons.

The optoelectronic and photonic properties of GaAs make it ideal for use in LEDs, laser diodes, photodetectors, and solar cells. Because of its operational quietness and resistance to radiation, GaAs is also used in highly sensitive aerospace and space electronics.

GaAs can also be found in very high-frequency and high-speed electronics such as monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMICs) and radio frequency components. These components are critical in mobile devices, communication infrastructure, and many other specialised systems.

The history of GaAs is somewhat complex. The discovery of Gallium is credited to the Frenchman Lecoq de Boisbaudran in 1875. The compound arsenide dates back to 1250 AD when it was discovered by Albertus Magnus, also known as Saint Albert the Great. Despite being discovered by such a luminary historical figure, arsenide was commonly used in rat poison.

It wasn’t until 1955 that scientists were able to grow a single crystal of GaAs suitable for building photocells. A decade later, the first GaAs-based field-effect transistor (MESFET) was developed by Carver Mead. During the 1970s, DARPA invested heavily in researching the applications of GaAs. This led to GaAs becoming integral to the development of laser‑guided munitions, miniaturised GPS receivers, and high‑frequency radar and communication systems.

Its unique properties gave GaAs the title of ‘the next great semiconductor material’. Unfortunately, the difficulties of producing GaAs at the purity required for semiconductors severely limit its use.

Most companies that can do so are based in either China or Japan. The production of GaAs requires processing arsenic, which is highly toxic, making it more difficult to manufacture and dispose of GaAs chips safely. Arsenide cannot use its oxide as an easy-to-use insulator like silicon does. Its brittleness and lack of a stable native oxide make manufacturing more complicated and expensive.

For now, GaAs remains ‘the semiconductor material that could’. The combination of high electron mobility, direct bandgap, high-frequency performance, and radiation tolerance makes it indispensable for specialised applications. But as the demand for technologies such as 5G, LEDs, and the Internet of Things (IoT) increases, so too will the need for GaAs semiconductors.

If the issues related to the cost, safety, environmental impact, and brittleness of GaAs chips

Silicon Carbide (SiC)

Third place in the hierarchy of semiconductor materials goes to silicon carbide (SiC). SiC is a compound semiconductor made of silicon and carbon and is now a key material in next-generation technologies.

SiC is not as universally dominant as silicon, but its use is growing. The robustness and high-voltage capability of SiC are making it increasingly important for high-power and energy-efficient applications.

The robustness and high-voltage capability of SiC are making it increasingly important for high-power and energy-efficient applications. A wide bandgap of ~3.2 eV means that SiC can operate at higher voltages, temperatures, and frequencies than Si alone. SiC can withstand higher current density and has lower leakage at high temperatures. And SiC chips have eight times the doping concentration when compared to Si chips.

Although it has only relatively recently risen to prominence as a semiconducting material, SiC has a long and somewhat colourful history.

Back in 1891, the American inventor Edward G. Acheson stumbled upon a new compound while trying to make artificial diamonds. After mixing clay and powdered coke in an iron bowl, Acheson thought he had discovered a new compound of carbon and alumina. He dubbed his discovery Carborundum and set about patenting it as an abrasive for use in gem polishing and knife sharpening.

SiC has a Mohs hardness rating of 9, making it almost as hard as a diamond. In fact, up until 1929, it was the hardest synthetic material available. It is still produced using much the same technique as Acheson did and is often used for more or less the same type of abrasive applications.

SiC also exists in natural form, although it is very rare. Naturally occurring SiC is called moissanite and is only found in meteorites.

Semiconductor-grade SiC is made by growing single-crystal SiC wafers using processes such as physical vapor transport (PVT) or sublimation growth. This process produces wafers with high thermal conductivity and wide bandgap properties suitable for power devices.

SiC has a wide bandgap of ~3.2 eV that eclipses silicon’s 1.12 eV. It also has high thermal conductivity (~3–4.9 W/cm·K) and a high breakdown electric field (~2–3 MV/cm). Its exceptional durability allows it to withstand extremely harsh environments and operate at temperatures above 200 °C.

SiC chips have an electron drift velocity twice that of SI chips, so they can switch much faster. They also lose up to 50% less energy in heat and can be manufactured much thinner than Si chips.

The rise of electric mobility and renewable energy has resulted in a surge in demand for SiC chips. If the application requires high power, high voltage, or high efficiency, then SiC offers a more workable, reliable solution than Si.

Lightweight power‑electronic modules using SiC, such as Schottky diodes, MOSFETs, and JFETs, are now integral for electric vehicles. SiC semiconductors are also used in renewable‑energy systems and for industrial power supplies, data-centre power modules, and as smart‑grid components.

Unfortunately, issues with SiC hold it back from taking first place. Eliminating defects in SiC crystals is incredibly difficult. SiC crystals are prone to triangular defects, basal plane dislocations, and edge dislocations, among other issues. Because it is so time-consuming to produce large, high-quality single crystals, SiC is considerably more expensive than Si.

SiC’s extreme hardness makes wafer slicing, polishing, and etching slower and more labour-intensive. It requires specialised fabrication processes, such as dry etching with high-energy plasma. All of which adds to the complexity and cost of manufacturing a SiC chip and impedes its widespread adoption.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/8d/e0/8de08e7cf8c954f00d30a4a1894a8294/0126807438v2.jpeg)

COMPARISON

Battle of SiC vs GaN power modules

Gallium Nitride (GaN)

Hot on the heels of SiC is another newcomer: gallium nitride (GaN). GaN is a wide-bandgap semiconductor made from gallium (Ga) and nitrogen (N). Its bandgap of ~3.4 eV means it can operate at higher voltages and temperatures than Si.

GaN is highly efficient and has a high switch rate. It’s commonly used in high-power, high-frequency, and optoelectronic applications. But just a short time ago, GaN was regarded as being too imperfect for use as a semiconductor.

The existence of gallium (Ga) was predicted in 1871 by the Russian chemist Dimitri Mendeleev. Four years later, the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran discovered the element.

It took another 57 years before scientists at the George Herbert Jones Laboratory in Chicago managed to synthesise GaN by causing a reaction between gallium metal and ammonia by heating the compound to 1,000 degrees Celsius. The synthesisation process was further refined in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

GaN had a big breakthrough in the early 1990s when Japanese researchers Shuji Nakamura, Isamu Akasaki, and Hiroshi Amano developed a method to produce high-brightness blue LEDs using GaN. This revolutionised photonics and earned the researchers a Nobel Prize.

The use of GaN for semiconductors didn’t appear until 2004, when Eudyna Device Inc. began to use GaN-based high electron mobility transistors (HEMTs) for RF purposes. In 2009, a plucky start-up called Efficient Power Conversion (EPC) introduced the first enhancement-mode GaN-on-silicon wafers for power MOSFET applications.

GaN has a combination of advantages that make it a highly attractive option for next‑generation electronics. It is a better conductor than Si by a magnitude of 1000. So GaN semiconductor chips can be made smaller and operate at a higher power without as much heat generation as Si chips. GaN has an electron mobility of 2,000 cm2/Vs, better than SiC’s 650 cm2/Vs and 30 times what Si can achieve.

GaN’s bandgap means it can reliably deliver more power at higher voltages without any loss of efficiency. GaN’s high electron mobility allows it to be used at high frequencies. Unlike Si, GaN copes well with RF applications beyond the GHz range.

These properties make GaN suitable for a wide range of applications. Everything from consumer electronics chargers to EV powertrains, data‑centre supplies, 5G infrastructure, and defence electronics now depends on GaN semiconductors.

GaN does have negative properties that put constraints on its use. GaN devices are built using epitaxial growth, where layers of GaN are built on silicon, silicon carbide, or other substrates. Defects and reliability issues can be caused by lattice mismatches and differences in thermal expansion. And although GaN can handle high heat, it has less thermal conduction than other wide-bandgap materials like SiC. GaN loses out to SiC when it comes to very high voltages. Anything above 600–1000 V can be challenging for a GaN-on-silicon power device.

GaN also has no P-types, which puts a major obstacle in its way of taking over Si or SiC at the top of the hierarchy. GaN naturally forms n-type layers easily, but creating stable p-type GaN is difficult. Electronic devices like CMOS logic circuits require both N-type and P-type regions. At the moment, the lack of P-types limits GaN’s ability to fully replace silicon or SiC in mainstream applications.

However, GaN is still one of the most important and promising third‑generation wide-bandgap semiconductor materials. As manufacturing processes improve, GaN could become more cost-effective and versatile.

GaN-on-GaN substrates are gaining momentum as a way to achieve higher-performance devices. Researchers are developing higher-power GaN devices, moving from 650 V toward 1200 V ratings. Reliability has improved in gate structures, particularly in enhancement-mode (E-mode) GaN devices. Many experts are betting that GaN is going to be one of the key materials shaping the future of semiconductors.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/97/19/9719983f8596dcb47f64dba9648c4dc5/0124622838v2.jpeg)

SEMICONDUCTOR MATERIALS

Germanium: The “lost” semiconductor

Germanium (Ge)

Before Si and well before any other materials emerged, germanium (Ge) was the star of semiconductors. A metalloid element with a crystalline structure, it has both high electrical conductivity and good thermal conductivity.

Ge itself was discovered in 1886 in Freiburg, Germany, by the scientist Clemens A. Winkler. Winkler identified Ge as a new element, confirmed its atomic weight, and detailed its chemical properties. What Winkler failed to uncover was Ge’s remarkable properties as a semiconductor.

It took over 60 years before Ge was recognised as an important semiconductor material. In fact, Ge has a special place in semiconductor history. The first Ge point-contact transistor was invented at Bell Labs by Bardeen, Brattain, and Shockley in 1947. This pivotal development is widely considered the birth of the modern semiconductor industry.

Ge has a bandgap energy of 0.7 eV, much lower than Si’s 1.1 bandgap. This gives Ge high carrier mobility for fast transistors and low-noise analogue devices. Ge also has good infrared absorption and a strong response in the near-IR and mid-IR range.

However, Ge’s moderate thermal conductivity limits its use in power electronics that run at high temperatures. And that’s not the only drawback. Ge atoms form covalent bonds that are slightly weaker than those in silicon’s crystal lattice. This makes it less able to withstand mechanical handling, bending, and thermal cycling. Ge’s brittleness also makes it more susceptible to defects and mechanical stress than Si. Plus, Ge is nowhere near as abundant as Si.

All this means that Ge cannot be scaled to large wafer diameters as easily or as cheaply as other options. Despite the excellent electronic properties that led to Ge being used in commercial transistors, diodes, high-frequency electronics, and infrared optics and detectors, the material is now mainly used in specialised, high-performance electronics.

These days, Ge is blended with Si to create SiGe semiconductor layers that have higher carrier mobility than pure silicon. SiGe semiconductors are found in high-performance CPUs and SoCs, 5G RF front ends and millimetre-wave circuits, as well as optical transceivers and silicon photonics. Because it offers much higher mobility than silicon, research is being conducted into Ge channel MOSFETs and Ge/III–V hybrid devices.

Ge’s importance as a semiconductor material has dwindled somewhat, but it could experience a resurgence in the very near future.

The Emerging Materials Shaping the Future of Semiconductors

As the race to produce ever more powerful microchips continues, researchers are constantly experimenting with other semiconductor materials. These emerging, advanced materials could be the foundation for the next leap forward in computing.

Here are four materials that could open up new directions for the digital age:

CSiGeSn: A recently developed semiconductor alloy composed of four elements: carbon (C), silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), and tin (Sn). All of these elements belong to Group IV of the periodic table. This makes the alloy highly compatible with existing CMOS‑based semiconductor manufacturing processes. CSiGeSn can also be finely tuned to adjust the bandgap, lattice constant, and other electronic/optical properties.

According to the inventors, CSiGeSn could enable “components beyond the capabilities of pure silicon.” This may include on‑chip photonic elements (lasers, detectors), quantum‑technology elements, or more versatile optoelectronic devices.

Unfortunately, many of the claims made around CSiGeSn have yet to be put to the test. While it is a potentially paradigm‑shifting material, there are still many challenges to overcome.

Gallium Oxide: Designated as an ultra‑wide bandgap (UWBG) semiconductor (approximately 4.8–4.9 eV), Ga2O3 has a very high breakdown electric field strength of around ~8 MV/cm. It’s viewed as a material that may surpass SiC and GaN for next‑generation power devices, high-voltage switches, power diodes, MOSFETs, Schottky diodes, and other applications needing high blocking voltage. A big plus is that theoretically Ga2O3 can be synthesised using a melt‑growth process, which could result in low-cost, large-area native substrates.

Researchers from Japan’s Nagoya University have recently solved a major manufacturing issue and produced the first reliable, working pn diodes using gallium oxide. While issues remain regarding defect control and its poor thermal conductivity, Ga₂O₃ has the potential to go far beyond the capabilities of current wide‑bandgap materials like GaN or SiC.

CVD Diamond: Synthetic diamonds made by the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process are another emerging high-performance semiconductor material. Their remarkably high thermal conductivity, high breakdown field, high-frequency performance, and very wide bandgap make CVD diamond stand out as a possible game changer. By taking hybrid approaches like GaN-on-diamond heterostructures, researchers have already found some applied uses for CVD diamond semiconductors.

However, diamond is difficult to dope for reliable N-type conductivity. It’s also extremely expensive to fabricate and would require fundamentally different processes, new tooling, and large re‑engineering.

At the time of writing, CVD diamond will likely be applied as a thermal-management partner or substrate/heat-spreader for UWBG semiconductors. However, if the practical challenges can be overcome, then it may see more widespread adoption.

2D Materials: 2D materials are crystalline sheets only one atom thick. They have unique electrical, mechanical, and optical properties. As silicon transistors hit their physical and scaling limits, 2D materials are increasingly seen as the next major semiconductor breakthrough.

There are currently two categories of 2D materials. The first is graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. Graphene is a zero-bandgap semiconductor, but it is extremely strong, flexible, and with excellent thermal conductivity.

Then there are transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), such as MoS2, WS2, and MoSe2. These materials have band gaps and behave like semiconductors.

2D materials could lead us to a post-silicon world. Theoretically, TMDs like MoS2 could enable ultra-small logic transistors beyond 1 nm and have the capability to integrate photonics and electronics in a single chip.

As of the time of writing, there are no practical and reliable manufacturable fabrication processes for semiconductors made of 2D material. But this may not be far away if recent investment and research from tech giants like Intel and TSMC is any indication.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/bf/73/bf73cb54fc3ded1ca5f8509d42e588e0/0125070459v2.jpeg)

PROJECT GENESIS

Minimizing the ecological footprint in Europe’s semiconductor industry

Towards the Future of Semiconductor Technology

Semiconductor technology is no longer dominated by a single material, but Si is still unmatched in cost, maturity, and integration density.

However, the alternatives are becoming ever more viable. The use of SiC is rapidly expanding in automotive and high-power markets. GaN is now common in fast chargers, RF, and emerging high-voltage power switching applications. GaAs and Ge are the best choices for photonics, IR sensing, and high-frequency electronics.

Ultra-wide-bandgap materials (Ga₂O₃, diamond) and 2D materials (graphene, MoS₂) may usher in the next generation of semiconductors, but only if the considerable manufacturing challenges can be overcome.

The future of semiconductors looks certain to be hybrid. Engineers, developers, and researchers will be able to choose from a diverse ecosystem of materials and select semiconductors that are precisely optimised for specific use cases. Customisation and hybridisation will result in semiconductors that are smaller, more powerful, and more robust than ever before.

(ID:50650683)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/bc/97/bc97cce107109a551f26fb8076ae1da8/0129190430v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ab/34/ab3461e7aabc1beab6f2598d09f1d9b4/0128949857v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cd/92/cd9200bfe196631a5fd7b5b85e25a5a6/0128944352v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/44/4d/444dda9649b5619c79d019c7dc1efcfc/0128974547v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b3/13/b313941dbf7adc57c6d144966106d82b/0129219607v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/56/a4/56a4d9b6ee131a7a00b8b89dabf108f9/0128979281v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/67/62/676279913d77e1db48eb5cbe9be4c767/0128937895v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0f/a2/0fa2b5bdc21e408fd73e637d226d5210/0128681532v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/7d/40/7d406bd959b3a9127c33a66157f9030a/0128339184v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/65/22/65223bc58811ced76adbfa7b5615d532/0129061536v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/20/ea20c0beb93f34ab43b28750644bbdca/0128983445v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/0a/b10a283cdf3e5f156781a7273c71a7e0/0129107484v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/30/cb30ebdca7fcaea281749cb396654eb3/0124716339v2.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/60/7e/607ec89d5d9b5/white-frame.jpg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/68/00/6800eb0040fb9/cobalt-vertical-aligned-bold.png)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/28/32/2832667c414aee61854700a7db3f2213/0127626188v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0c/71/0c7136f0406689ac88a83b3d5c9404c8/0123816960v2.jpeg)