UNDERSTANDING HIGH ELECTRON MOBILITY TRANSISTORS Answering 24 questions about HEMTs you never dared to ask

Related Vendors

This article introduces the technology of so-called HEMTs or high electron mobility transistors. These devices represent an important evolution in transistor design and have become key components in modern high-frequency and microwave electronics. Thanks to their outstanding performance, HEMTs are widely used in low-noise amplifiers (LNAs) as well as in power applications.

In this question–answer format, we will move from the basic concepts of semiconductor physics to more specific aspects related to the operation of this fascinating device, as well as to the materials from which it is made.

Let's start.

1. What is a HEMT (High Electron Mobility Transistor)?

A high electron mobility transistor is a kind of field-effect transistor (FET) based on a heterojunction, a junction of semiconductors with different bandgaps. This junction may become a very complex structure made of layers of those semiconductors.

Typically, the materials used to produce HEMTS have been gallium arsenide, GaAs and aluminum-gallium arsenide, AlGaAs. This device was developed as a substitute for GaAs MESFET (metal-semiconductor junction field-effect transistor) to improve its performance8. The MESFET was regularly used in microwave amplifiers during the 1980’s and 1990’s. We could therefore say that a HEMT is a high efficiency variation of a MESFET.

2. What other ways can we name a HEMT?

A high electron mobility transistor or HEMT can also be found in the bibliography in the following ways11,13:

- TEGFET: Two-dimensional Electron Gas Field-Effect Transistor

- MODFET: MOdulation Doped Field-Effect Transistor

- HFET: Heterojunction Field-Effect Transistor

3. Who developed this device for the first time?

It was Dr. Takashi Mimura and his group from FUJITSU Laboratories in 1979 the first who successfully developed the HEMT device. Dr. Takashi Mimura graduated in 1970 from Graduate School of Engineering Science in Osaka University, where he received his PhD in engineering in 1982.3,19

4. What is the physical structure of a HEMT?

A HEMT is a kind of field-effect transistor in which conduction does not take place in a channel under the gate electrode, as in a conventional FET transistor, but relies on a thin layer with a high concentration of electrons called 2DEG (two-dimensional electron gas).

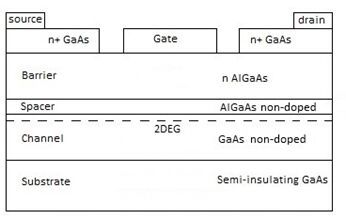

As we can see in the next picture (see Fig.1), a conventional HEMT is made of the following layer structure8:

- An AlGaAs layer doped with silicon donor atoms (n-type), called barrier layer or charge supply layer: it is used as donor of free electrons to the channel.

- An undoped AlGaAs layer called spacer layer8.

- An undoped GaAs layer called channel layer: this layer could also be made of p-type GaAs. It is grown on a GaAs semi-insulating substrate.

- Source (S) and drain (D) electrodes: highly doped GaAs layers are diffused (ohmic contacts) with the idea that the access resistance at source and drain are as small as possible.

- Gate contact (G): it consists of a Schottky junction (metal-semiconductor) like in a MESFET, with rectifying features.

The device surface undergoes a passivation or insulation process through the deposit of a dielectric8; in the case of GaAs devices silicon nitride (Si3N4) is used, given that GaAs does not have a native oxide as it happens with silicon. But the interesting thing with this structure is that under the gate contact we have a high bandgap semiconductor layer just over a lower bandgap semiconductor layer:

- The bandgap of AlGaAs ranges from about 1,42 and 2,16eV (depending on the aluminum content, Al).

- The bandgap of GaAs is 1,42eV.

The next figure (see Fig.2) shows a somewhat more complete structure of a HEMT, in which drain and source contacts reach the 2DEG layer16; in addition, we can see a GaAs buffer layer placed between the substrate and the channel layer:

![Fig.2 A more complete structure of HEMT.(Source: Setty 2021, [16]) Fig.2 A more complete structure of HEMT.(Source: Setty 2021, [16])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/ileXJR0VqAvTO6SzOa2RQ0xWZFk=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/77/80/77806444e5ff23a2b40e4d805f82f6d3/0127622283v1.jpeg)

5. How does a HEMT work?

In a HEMT the electrons from the doped AlGaAs layer tend to diffuse towards the GaAs layer creating a conduction channel near the AlGaAs/GaAs interface; this is what we call two-dimensional electron gas or 2DEG. Here the electrons are confined, and they move along a two-dimensional plane parallel to the heterojunction8,11.

This two-dimensional electron gas of nanometer scale constitutes an electronic inversion layer11, that is, a region where the minority carrier concentration is bigger than the majority carrier concentration (in equilibrium). If the lower bandgap semiconductor is low-doped (or if it is not doped at all, as in Fig.1), the electron mobility of the inversion layer will be great. Consequently, the 2DEG layer will be responsible for the conduction in the device.

Because of the gap between the electron-supply layer (AlGaAs) and the non-doped layer (GaAs) along with the electron confinement in an extremely thin interface, it is possible to reduce coulomb scattering8, the phenomenon which slows down electrons on their movement from source to drain. Thanks to this, we can achieve high operating speed and high electron mobility.

6. What does a high electron mobility imply?

It implies very short transit times between source and drain, high operating speeds and thus, very high operating frequencies. These features make this device suitable for use in the microwave range of frequencies.

7. How is the band structure in a HEMT?

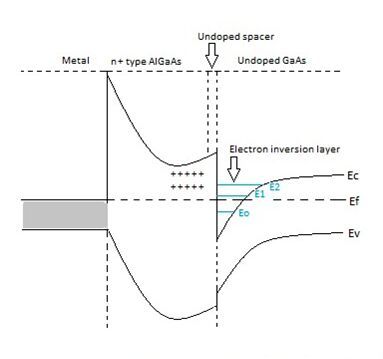

The energy band diagram of a classic HEMT is as follows8,11 (see Fig.3):

Given the difference in bandgaps, we can observe the present discontinuity between the highly doped AlGaAs layer and the non-doped GaAs layer. On the other hand, the electronic inversion layer constitutes what comes to be called a potential well (a triangular well, in this case) in which the electron energy levels are quantized (E0, E0, E0)11. Since the electrons tend to occupy the lowest energy states, they head toward this potential well forming in this way the 2DEG confined within the channel.

8. How do we operate this device?

The functioning of this device is like the MESFET, that is, we control the source to drain current by means of a voltage applied to the gate electrode, a voltage which modulates the inversion layer conductivity. By applying positive gate voltages, the depth of the potential well increases giving rise to a bigger concentration of electrons; in other words, the electron density in 2DEG layer increases (or sheet carrier density, ns)11.

The drain current in an ideal HEMT is proportional to channel width wch , to the electron density in 2DEG layer (ns) and to saturation velocity vsat, as we can see in the expression below11:

ID=q·wch·ns· vsat

9. What is the concept of modulation doping?

Inside a HEMT there is a heterojunction formed by the system AlGaAs/GaAs, having a high bandgap and highly doped material (AlGaAs); at steady state the electrons associated with the AlGaAs donor impurities can “see” lower energy states inside the lower bandgap material, thus resulting in a transfer of electrons to this GaAs layer. Additionally, the gap between positively charged donors and electrons creates an electric field which bends the energy bands.

So, this is the concept of modulation doping8: we impurify the AlGaAs layer to provide the necessary carriers leaving a spacer layer without doping and, finally, we do not dope the GaAs layer in order to reduce coulomb scattering and to increase carrier velocity.

10. What are the advantages of modulation doping?

We can solve (or at least reduce) two problems: free electrons scattering and carrier freeze-out. Let us analyze both points in detail.

On the one hand, there is the problem of free electrons scattering (or coulomb scattering). In a semiconductor the ionized impurities give rise to fixed charge centers11,13(DX centers) which are responsible for the dispersion of free electrons; as we mentioned before, with the current gap between the electrons and these ionized DX centers we are able to remove or reduce the scattering, and even more when we introduce in the structure a non-doped spacer layer, as will be commented later. With little or no scattering, the electronic mobility dramatically increases.

On the other hand, we also solve another problem present with doping, that is the so-called carrier freeze-out. For that purpose, let’s consider the following picture (see Fig.4) which shows the free electrons density as a function of temperature (in this particular case, for a silicon sample with a donor impurity concentration of 1015cm-3):

![Fig.4 Electron density as a function of temperature.(Source: Singh 2001, [18]) Fig.4 Electron density as a function of temperature.(Source: Singh 2001, [18])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/eWt94ZJ7FfuREEcv5oq-S50esrk=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/fe/befe5238ab5f4212fd553ebdb5bfcf21/0127622705v1.jpeg)

At low temperatures (freezeout range) all the electrons are confined in donor atoms, so that there is little free electrons density. As temperature rises, the number of ionized donors increases (in other words, electrons that leave the donor atoms and become free electrons in the conduction band) to the point where all the donors are ionized; at this point free electrons density equals donor density (this is what comes to be called saturation range)18.

Because of modulation doping, electrons are in low energy states and remain mobile even at very low temperatures; that is why we can achieve very high electron densities which are maintained at these low temperatures.

11. What happens with HEMTs and cryogenic temperatures?

In radio astronomy, it comes to detecting extremely faint signals emitted by objects far away from earth, so highly sensitive receivers are needed devoted to this task. That is to say, the noise level generated by these receivers should be the minimum.

These devices generate less noise when cooled, so that’s why they are usually refrigerated at extremely cold temperatures4. These levels below -150ºC are the so-called cryogenic temperatures. Having said this, a HEMT which works at cryogenic temperatures will have bigger electronic mobility, less noise (thermal noise is minimized (*) due to low temperatures) and an improved performance.

The use of cryogenic temperatures extends to satellite communication systems as well as in specific scientific instrumentation.

(*) Let us remember that, because of random movement of charge carriers, any device at any temperature bigger than absolute zero (-273K), generates thermal noise. The thermal noise power can be expressed in the following way:

N=kTB

where K= Boltzmann constant (1,38x10-23J/K), T=temperature (Kelvin) y B= bandwidth (Hz) in which noise is measured.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/04/3e/043e41b0fefa95f216052ed236827cec/0121098409v2.jpeg)

POWER TRANSISTORS

GaN HEMT Vs SiC MOSFET: Brief Comparison

12. Which is the process by which a 2DEG is created?

Now we are going to analyze in detail the formation process of 2DEG layer. The understanding of the energy band structure in a semiconductor can become little intuitive and somewhat abstract; for the case of a HEMT we will try to address it as simple as possible. To this end, let us check the next figure (see Fig.5) related to the case of a gallium nitride HEMT (GaN HEMT):

![Fig.5 Formation process of 2DEG, case of a GaN HEMT.(Source: Xiao-Guang 2015, [4]) Fig.5 Formation process of 2DEG, case of a GaN HEMT.(Source: Xiao-Guang 2015, [4])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/HH_IhELAvz3xqNFz8FkcjtJB7zA=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/40/3e/403e4731bc67c46ae4d2a68e1693afd4/0127775318v1.jpeg)

If we consider an n-doped AlGaN semiconductor layer over a non-doped GaN layer (see Fig.5a), in the AlGaN layer a polarization is induced so that the negative charges would be in the upper part and the positive charges would be in the interface between both semiconductors; in other words, we have an electric field placed inside AlGaN layer4.

This polarization leads to a bending of the energy bands, turning towards the AlGaN/GaN interface (see Fig.5b). We could see the same effect if a voltage is applied to this structure. The applied field makes the free electrons (left side) flow towards the positive pole of the electric field (right side), leaving positive charges in the negative pole. Both positive and negative charges generate an electric field which reduces the original one, making the slope of the energy bands round up as well as the Fermi level is stabilized (see Fig.5c).

If we join the AlGaN layer with a lower bandgap semiconductor (see Fig.5d), the Fermi level tends to align between them in a way that the electrons gathered in the bottom of AlGaN flow towards the upper part of the GaN layer, thereby creating the 2DEG layer4 (see Fig.5e).

This 2DEG constitutes a triangular potential well11 where the electrons can rapidly move and from where they cannot escape; so there is a great concentration of high mobility electrons and, given that they are in a non-doped semiconductor layer, there will be no impurities to collide with.

13. Inside a HEMT structure, what is exactly the function of the spacer layer?

The non-doped AlGaAs layer allows us to establish a spacing between impurities and charge carriers (that is, we separate the channel from the impurities); it can be said that we “shield” the present electric field in the barrier layer and, in doing so, the scattering effect with ionized impurities11is reduced and so, electronic mobility is improved.

14. What is the main problem with a conventional HEMT?

The main issue we face with HEMTs is what comes to be called DX centers (deep centers) located in the middle of the bandgap of AlGaAs barrier layer. To dope this layer, silicon is used as a donor and this results in states inside the bandgap that trap free electrons (that is, DX center trapping effect). This effect becomes bigger as the aluminum concentration increases in this layer, limiting it to a value between 20 and 25%13. This issue affects the number of electrons injected into the 2DEG layer, thus making the AlGaAs HEMT a low current device.

DX centers are consequently related to the interaction between aluminum and silicon atoms in AlGaAs barrier layer13.

15. What is the solutions to the problem with a conventional HEMT?

We find several solutions to improve anomalies due to deep centers, low power and other drawbacks. They are the following8,13:

- The use of another kind of semiconductor for the barrier layer.

- pHEMT technology (or pseudomorfic HEMT).

- Inverted structure.

- Double 2DEG.

- Superlattices.

Now let us discuss each one of these solutions in more detail.

16. Why should we use another type of semiconductor for the barrier layer

When we introduce indium (In) inside a HEMT device, that is, if we use InAlAs instead of AlGaAs (barrier layer) we shall be free of DX centers. This in turn implies the replacement of GaAs for InGaAs and to grow the whole structure on an indium phosphide (InP) substrate, to achieve the matching of crystal lattices13.

Based on this, the layer where conduction happens (2DEG) is made of InGaAs: this material has an electronic mobility in the order of 10.000cm2/Vs, which is really high and bigger than GaAs (around 8500cm2/Vs). So this feature gives to this device outstanding properties regarding electronic mobility, at both ambient and very low temperatures. Additionally, the application of a very high doping in the InAlAs barrier layer (delta-doping technique or planar doping)13 provides high electron densities to the channel. In the following picture (see Fig.6) we can see an example of InP HEMT:

![Fig.6 InP HEMT structure.(Source: ETH Zürich, MWE, [2]) Fig.6 InP HEMT structure.(Source: ETH Zürich, MWE, [2])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/omVSO97V8nQx_w_ujBrD2vUGLto=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/44/aa/44aa31375e235058bcbe65a3bd35a078/0127622729v1.jpeg)

In this structure we can note that the gate terminal has been designed with “T” shape, which allows to reduce the gate resistance due to the increase of cross section of the gate. This design also provides a shorter gate length2.

17. What is pHEMT technology or pseudomorfic HEMT?

The so-called pHEMT o pseudomorfic HEMT is based on the incorporation of a very thin layer of InGaAs between the doped AlGaAs layer (barrier layer) and the non-doped GaAs layer (channel layer). Since this InGaAs layer has a lower bandgap than GaAs, an artificial potential well is formed where the electrons will move. The advantages we get with this structure are bigger electronic mobility and higher saturation velocity.

The reason for using a highly thin layer lies in the difference between lattice constants of InGaAs and GaAs, difference that hinders the growth of the first layer over the second13. Let us remember that the smallest atomic structure we can define in a semiconductor is the primitive cell, which would be a cube of dimensions or side “a”, called lattice constant16.

GaAs has a lattice constant of 5,65Å (angstroms) while InGaAs constant can range depending on the proportion of In. We may solve this difference between lattice constants if we are able to grow only an extremely thin and strained layer, a layer which adopts the lattice structure of GaAs13. This epitaxial stretched layer that adapts to the substrate lattice constant is called pseudomorphic layer and is where electrons are confined (2DEG).

The following figure graphically shows what we have just discussed (see Fig.7):

![Fig.7 Formation of pseudomorphic layer.(Source: Setty 2021, [16]) Fig.7 Formation of pseudomorphic layer.(Source: Setty 2021, [16])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/ZMDdbZdon9xhCYuLTgkP6kFCet8=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/24/1c/241ccdad42dbf83fb5b11b428b1b8b58/0127622736v1.jpeg)

We may find GaAs-based pHEMTs but also InP-based pHEMTs. In the next picture (see Fig.8) we see a basic structure of a GaAs-based pHEM1:

18. What is an inverted structure in a HEMT?

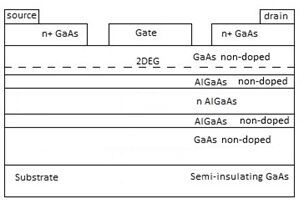

In a HEMT with inverted structure we turn the order of the layers, as we see in the following picture8 (see Fig.9). In doing so, we bring the 2DEG channel closer to the gate and the electrons that may be present in the substrate will not enter the channel. This configuration allows to increase the current capability and transconductance; however, the disadvantages we get are a bigger gate capacity and lower transition frequency, fT.

19. What is a double 2DEG HEMT?

To increase the power of the device, in a conventional HEMT we can add another doped AlGaAs layer under the non-doped GaAs, obtaining in this way a channel layer with double 2DEG bounded by 2 AlGaAs layers8.

This results in bigger electron density and higher currents, for the same applied voltage. The interesting thing is that this current growth enables the rise of the switching frequency and hence, the circuit performance.

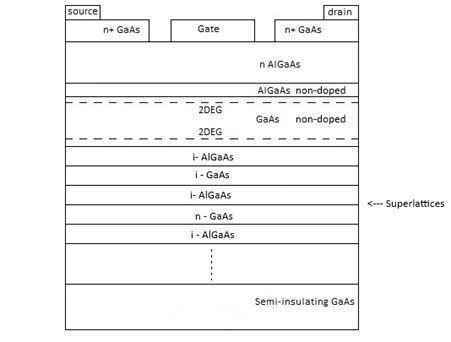

20. What are the superlattices? And what are their features?

Consider a HEMT with double 2DEG in which we replace the doped AlGaAs layer by a superlattice; as a result we will obtain better performances. We may define a superlattice as a succession of extremely thin and alternating intrinsic AlGaAs and doped GaAs layers8 or also, intrinsic AlGaAs and intrinsic GaAs layers.

In the following picture (see Fig.10) a basic scheme of a superlattice-based HEMT is shown8:

Now let us discuss some characteristics and/or advantages of superlattices in more detail:

- Inside a superlattice the electrons propagate through the different layers in the same way that they do through the atomic structure of a semiconductor13.

- As we saw before, the DX centers issue limits the supply of electrons to the 2DEG layer; using superlattices we can reduce this problem given that we physically separate the silicon donor atoms from the aluminum atoms.

- In this sandwich-type AlGaAs/GaAs/AlGaAs structure, the electrons are found inside the well formed by the central layer and where they cannot escape given that the depth of the well (in eV) is much bigger than the thermal energy of the electrons (25meV at room temperature). Nevertheless, if the AlGaAs barrier is thin enough the electrons can pass through it by tunnel effect and reach the 2DEG layer (electron tunnelling)13.

- The well described before has several states or energy levels from and to where the electrons can move; this scenario occurs when the electrons are confined in a very small space, of atomic dimensions13.

21. Which are the most frequent applications of HEMTs?

As we have stated before, in HEMTs the intrinsic characteristic of electronic mobility makes them ideal for applications in the microwave (1-30GHz) and millimeter-wave ranges (30-300GHz): wireless communications systems (cellular phones, base transceiver stations), satellite communications systems, GPS receivers, radar systems and electronic warfare applications, among others.

HEMTs are also characterized by their low noise level, hence they find application in the design of low noise amplifiers (LNAs), for instance in radio astronomy receivers. HEMTs are used as well in power amplifiers10.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/60/c3/60c30b660b640/christian-schwabe-new-reliability-aspects-for-power-devices-in-application.jpeg)

22. Which are the most frequent applications of pHEMTs?

pHEMTs (pseudomorphic high-electron-mobility-transistors) are commonly used in monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMIC)16 because of their excellent features such as low noise figure, high OIP3 (*) and outstanding performance in microwave and higher frequencies

(*) OIP3: Output Intercept Point of the 3rd order. In an amplifier, a high OIP3 states better linearity, less distortion and less generation of spurious signals.

Finally, and even a bit superficially, we cannot leave without mention the current technology that for some years has entered the scene and revolutionized power electronics and many fields, displacing silicon in many applications. We are talking about wide bandgap semiconductors (WBS from now on). These types of semiconductors are known for a bandgap greater than 2eV (for comparison, silicon has a bandgap of 1,12eV). In relation to this, we can establish the following classification12 (see Table 1):

Table 1. Classification of materials according to its bandgap

| Bandgap (eV) | Material | Examples |

| 0 | Conductor | Cu, Al |

| < 2 | Semiconductor (single element or compound semiconductor) | Ge, Si, InAs, InP, GaAs |

| >2 | Wide bandgap semiconductors | SiC, ZnO, GaN |

| >4 | Insulators | Diamond |

Now let us review briefly some important questions of the WBS applied to HEMTs.

23. Why do we use wide bandgap semiconductors? What advantages do they offer over silicon-based devices?

The more widely known and used WBS are definitely gallium nitride (GaN) and silicon carbide (SiC). The first one is a III-V compound semiconductor (one element from group III and another element from group V) and the second one is a IV-IV compound semiconductor.

Compared to silicon, the electrical and thermal properties of WBS are superior. The next table can help us answer these questions (see Table 2):

Table 2. Characteristics of WBS

| Properties | Effect-Outcome |

| Bigger bandgap |

Higher operating temperatures |

| Higher thermal conductivity | |

|

Higher electronic saturation velocity | Lower losses (smaller RON, resistance in conduction state) |

| Higher operating frequencies | |

| Bigger breakdown electric field | Higher operating voltage |

In the following table we can compare some features of semiconductors such as GaN, SiC y GaAs in relation to silicon5,17 (see table 3):

Table 3. Properties of some well-known semiconductors

| Properties

| Si | GaAs | GaN | 4H-SiC (1) |

| Electronic Mobility (cm2/Vs) | 1400 | 8500 | 1500 | 900 |

| Bandgap (eV) | 1.12 | 1.42 | 3.39 | 3.265 |

| Power density (W/mm) | 0.2 | 0.5 | >30 | 10 |

| Thermal conductivity (@300K) (W/cmK) | 1.3-1.5 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 4.9 |

| Breakdown voltaje, Ec (kV/cm) | 300 | 400 | 3300 | 2200 |

- In the case of silicon carbide, its bandgap depends on the polytype: the most used is 4H-SiC.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/62/a0/62a0941bd00c0/pcim-best-paper-awards-winner-matthias-kasper.jpeg)

24. And finally, what about GaN HEMTs?

An attempt to cover GaN HEMTs in detail would require the dedication of entire books, so in this section we are only going to highlight several points of interest.

Gallium nitride is a resistant and mechanically stable material. As a power device, its characteristics exceed their equivalents in silicon: greater breakdown voltage, faster switching speed15and smaller RON.

GaN devices can grow on different kinds of substrates: silicon, silicon carbide, sapphire, diamond. Because of the cost of materials and processes, GaN HEMTs with silicon substrate (GaN-on- Si) could be defined as the low-cost version of GaN HEMTs. On the other hand, GaN HEMTs with SiC substrate (GaN-on-SiC) allow better thermal heat dissipation, given the high thermal conductivity of SiC15 (see table 3). The growth time needed in the case of SiC (substrate growing time) is far slower than in the case of Si, for that reason GaN-on-SiC devices do not stand out, in general terms, by large-scale commercial use but in specific applications such as defense and power devices, among others.

Now let us revisit some examples of GaN HEMTs. In the following picture (see Fig.11) we can observe the basic structure of a GaN HEMT, in which the 2DEG is formed in the interface between intrinsic GaN and AlGaN layers:

![Fig.11 Basic structure of a GaN HEMT.(Source: Joshin 2014, [9]) Fig.11 Basic structure of a GaN HEMT.(Source: Joshin 2014, [9])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/FFMQVFuyZ27ASEBhgB5Bcnp_VtM=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0f/4b/0f4bc073ffeb0b3443467f82a57b4b5e/0127622749v1.jpeg)

Lastly, in the next figure (see Fig.12) we can see a GaN HEMT structure where a field-plate is included, a kind of structure that manages to improve the device’s electric performance and the power level (increase in efficiency). The function of this field-plate is therefore to reshape the electric field distribution profile between the gate and drain terminals20 in the case of Fig.12). Several advantages are obtained with field-plates, among others, bigger breakdown voltage and the reduction of electron-trapping effect on the surface of the device:

![Fig.12 Cross-section of a GaN HEMT which includes a field-plate.(Source: Vacca 2013, [20]) Fig.12 Cross-section of a GaN HEMT which includes a field-plate.(Source: Vacca 2013, [20])](https://cdn1.vogel.de/kV2NqOF1__-7PceRijdXvYhkyUY=/fit-in/540x0/smart/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/34/a2/34a27331b7c36b7e2f915661ac6abfd1/0127622752v1.jpeg)

References

- 1. Es-Saqy, 5G mm-wave Band pHEMT VCO with Ultralow PN, Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal Vol. 5, No. 3, 487-492 (2020).

- 2. ETH Zürich. Millimeter-Wave Electronics laboratory (MWE). Indium Phosphide (InP) HEMTs.

- 3. Fujitsu Laboratories Ltd. Fujitsu Laboratories' Honorary Fellow Takashi Mimura Honored with Kyoto Prize for HEMT Invention.

- 4. He Xiao-Guang, Zhao De-Gang, Jiang De-Sheng. Formation of two-dimensional electron gas at AlGaN/GaN heterostructure and the derivation of its sheet density expression. Chinese Physics B, 2015.

- 5. Hindle, Patrick. 2010 GaAs Foundry Services Outlook, Microwave Journal Magazine, June 2010.

- 6. National Geographic Institute, Astronomy and Technological Developments – Low Noise Cryogenic Amplifiers.

- 7. Jack Browne, Trying to Keep the Noise Down. Microwaves & RF Magazine, August 2017.

- 8. Jiménez Tejada, J.A. Microwave Integrated Circuits and Devices. Electronic Engineering, Lecture Notes. University of Granada, 1996.

- 9. Joshin, K., Kikkawa T., Mashuda S., Watanabe K. Outlook for GaN HEMT Technology, FUJITSU Sci. Tech. J., 2014.

- 10. Laverguetta, Thomas S. Microwaves and wireless simplified, 2nd edition. Artech House, 2005.

- 11. Luy, Johann-F. Microwave Semiconductor Devices. Theory, Technology and Performance. Expert Verlag, 2006.

- 12. Mouser, Reference Guide to Wide Bandgap Semiconductors, Mouser Electronics Inc., 2023.

- 13. Orton, John. Semiconductors and the Information Revolution: Magic Crystals that made IT Happen. Elsevier, 2009.

- 14. Pengelly, Raymond S. A Review of GaN on SiC High Electron-Mobility Power Transistors and MMICs. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, 2012.

- 15. Schweber, Bill. Cómo los HEMT de GaN pueden ayudarle a aumentar la eficiencia de la fuente de alimentación, DigiKey, 2023.

- 16. Setty, Radha. MMIC Technologies: Pseudomorphic High Electron Mobility Transistor (pHEMT), Mini-Circuits, 2021.

- 17. Singh, Jasprit. Optoelectronics. An Introduction to Materials and Devices. McGraw-Hill International Editions. Electrical Engineering Series, 1996.

- 18. Singh, Jasprit. Semiconductor Devices: Basic Principles. John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2001.

- 19. The University of Osaka. Revolutionizing the World of Communications through Transistors. Success Comes with its Fair Share of Challenges.

- 20. Vacca, G. GaN-based HEMT improvement using advanced structures. Semiconductor Today Magazine. Compounds & Advanced Silicon, Sept. 2013.

(ID:50608483)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/thumbor.vogel.de/eFG69EpuHKhuaAGzhO7BZfNp8Ns=/500x500/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/69/00/6900968a8c1d0/afs.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/68/00/6800eb0040fb9/cobalt-vertical-aligned-bold.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/66/8b/668becd1c07eb/dowa-logo-word--1-.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/7d/40/7d406bd959b3a9127c33a66157f9030a/0128339184v4.jpeg)