ENERGY SYSTEMS The role of power electronics in next-generation energy harvesting systems

Related Vendors

Power electronics make energy harvesting practical by handling low, unstable inputs and managing storage, conversion, and control. Success depends on system-level design that balances efficiency, size, and reliability under real-world conditions.

Devices are getting smaller, more connected, and more widely distributed, especially in industrial monitoring, wearables, and remote sensing. These systems often end up in places where running wires isn’t practical and swapping batteries regularly isn’t realistic. To keep them operating long term, you need a power source that works in the background with little to no maintenance. That’s the main reason energy harvesting is getting more attention.

Instead of depending on batteries, energy harvesting systems collect small amounts of energy from the environment and use it to power electronics. It sounds simple enough, but the energy available from these sources is limited and unstable. To make use of it, you need more than just a transducer; you need electronics that can convert that energy into a form that devices can use consistently.

This is where power electronics matter. These circuits handle voltage conversion, power conditioning, energy storage, and system startup. They make sure that even when energy input is weak or intermittent, the device keeps working. Without well-designed power electronics, most of the energy that’s harvested would be wasted.

This article looks at how energy harvesting works in practice, with a focus on the design challenges at the interface between the energy source and the load. The aim is to break down where power electronics fit in, why they’re needed, and how they’re evolving to support a growing set of energy harvesting applications.

Architecture of an energy harvesting system

An energy harvesting system has four constituent parts. Each one plays a specific role in converting ambient energy into usable power for low-energy electronics. Here’s how they fit together:

Energy transducer

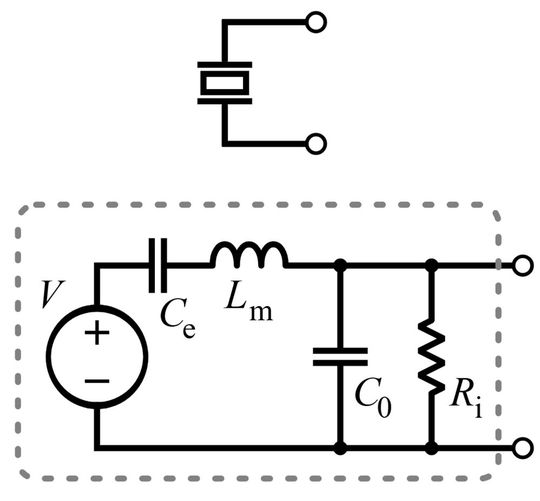

This is the part that captures energy from the environment and turns it into electricity. Common types include solar cells, thermoelectric generators, piezoelectric elements, and RF antennas. Each one works best in specific conditions and produces energy at different voltage and power levels.

Power conditioning circuit

This is where power electronics come in. The energy from the transducer is usually unstable or too low in voltage to be useful directly. Power conditioning handles that. It includes rectifiers, voltage converters, regulators, and sometimes maximum power point tracking. This circuit needs to start from very low input voltages, often less than a volt, and deliver consistent output to the load or storage.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/f3/7c/f37cd0a589fcb97dd376844aaf602631/94126563.jpeg)

ENERGY STORAGE

A look at the main applications of energy storage systems

Energy storage

Because ambient sources are inconsistent (sunlight fades, vibrations stop, RF signals drop), you need to store energy when it’s available and use it when it’s not. This can be done with rechargeable batteries, supercapacitors, or a hybrid of both. The choice depends on the energy profile of the source and the power needs of the load.

The load

This is the actual device being powered. That could be a sensor, a transmitter, a microcontroller, or some combination of those. The load determines how much energy you need and how consistently you need it. That, in turn, shapes how you design the rest of the system.

A successful energy harvesting setup balances all of these parts. You can’t look at them in isolation. The transducer might be efficient, but if the power electronics can’t handle low voltages or if storage can’t hold enough charge, the system won’t perform well. Every part of the architecture has to work with the limitations and variability of the others.

Energy sources and conversion technologies

Energy harvesting depends entirely on what kind of energy is available around your device. The options fall into four main categories: mechanical, thermal, solar, and RF. Each has specific advantages and trade-offs depending on the environment and the energy needs of your system.

- Mechanical and vibrational energy sources, for example, rely on motion or stress to generate electricity. You can do this using piezoelectric materials that create charge when deformed, electromagnetic systems that move a magnet through a coil, or electrostatic setups that change capacitance with movement.

- Thermal energy can be harvested from temperature differences using thermoelectric generators or from time-based temperature changes using pyroelectric materials. Thermoelectric generators are simple and reliable but need a decent temperature gradient to produce useful power.

- Photovoltaic energy harvesting is well known and widely used. Solar cells are effective outdoors and can also generate some power from indoor lighting, although efficiency drops significantly. They’re easy to implement and generally stable, but they require surface area and exposure to light, which isn’t always an option, especially in embedded or mobile systems.

- RF energy harvesting captures ambient electromagnetic radiation from sources like Wi-Fi routers, cellular signals, or broadcast towers. This method has the advantage of working without physical contact or light exposure. However, the power levels are extremely low, especially as distance increases.

None of these sources is perfect. Most provide low and variable power, so your system design needs to account for that. Often, you’ll get better results by combining multiple sources. A hybrid setup, like a solar panel with a vibration harvester, gives more consistent output but adds complexity to the conditioning and control circuits.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/9c/f3/9cf3d22025c978a431f712e0b82b4e73/95479955.jpeg)

BASIC KNOWLEDGE

Everything you need to know about photovoltaics

Power electronics behind the scenes

Most of the attention in energy harvesting goes to the transducers and the energy sources. But in practice, the electronics between the source and the load decide how well your system performs. You’re working with unstable inputs, low voltages, and unpredictable availability, so the circuits in the middle need to do more than just pass power along.

One area that’s getting more attention is how systems start up from zero. Many harvesting sources can’t produce usable voltage until after the power electronics are running, which creates a chicken-and-egg problem. Newer designs solve this with self-starting circuits that can bootstrap from millivolt inputs. These designs prioritize startup before regulation, using passive components and ultra-low-threshold transistors to get the system moving before more sophisticated control logic kicks in.

Another focus is on adaptive behavior. Harvested energy changes constantly: solar with cloud cover, vibration with machine speed, and RF with network activity. Instead of fixed conversion settings, some systems now monitor input characteristics and adjust their internal parameters in real time. That might mean switching operating modes, adjusting switching frequency, or dynamically changing load behavior based on storage levels and expected input.

Finally, integration is becoming more important. Rather than assembling systems from multiple discrete chips, designers are moving toward system-on-chip (SoC) and system-in-package (SiP) solutions. These combine energy harvesting inputs, voltage conversion, energy management, and sometimes even wireless communication into one footprint. This reduces size, loss, and complexity — important when your total energy budget is a few microwatts per hour.

These trends aren’t visible on the datasheet for a harvester or sensor. But they’re what make energy harvesting systems practical and reliable, especially in devices that have to work without intervention for years at a time. If any part of that chain fails, the whole system stops working, no matter how much energy is technically available.

Integration challenges and engineering trade-offs

Energy harvesting systems sound simple on paper, but real-world conditions expose the limits quickly. The biggest challenge is working with low and unpredictable input power. Many transducers output just tens of millivolts, too little for standard converters. You need boost circuits that can start at low voltages, and they often trade efficiency for reliability.

Impedance mismatch is another issue. A harvester’s internal resistance varies with conditions. If the load doesn’t match, you waste energy. Some systems use adaptive impedance matching, but this adds circuit complexity and power overhead.

Storage adds more constraints. Supercapacitors leak. Batteries degrade. Cold-starting a system from zero energy is still a design hurdle. Hybrid storage setups can help, but they need careful control to avoid energy losses and extend component life. Space and packaging also limit how much hardware you can use. Smaller devices have less room for transducers and storage, and less thermal headroom. Integrating everything helps with size but makes the system harder to optimize or replace.

In the end, it’s about trade-offs. You have to decide what matters most for your use case (uptime, lifetime, size, or cost) and build around that. You won’t get everything, so the design has to reflect your priorities.

PCIM Expo 2025: Join the industry highlight

Position your company at the forefront of the power electronics industry! Exhibit at the PCIM Expo 2025 in Nuremberg, Germany to showcase your solutions and connect with top decision-makers and innovators driving the industry forward.

Learn more

(ID:50399114)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/71/fd/71fdcc22d9a9bd2f42985f692c4aefa2/0128924236v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/94/54/94548eaecd020681e558d563bc48ba1d/0128926221v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/29/99/2999bb9af245dd31f4c837c1d9359046/0128923137v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/10/78/107856328ef320cc081bf88e0baf95e8/0128685487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/67/62/676279913d77e1db48eb5cbe9be4c767/0128937895v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0f/a2/0fa2b5bdc21e408fd73e637d226d5210/0128681532v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4f/6f/4f6faf0ca6f748a2967d6b5bba7c88e1/0128682406v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ad/52/ad52f7b5542eff15ba54ec354d31b50d/0128681536v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/1e/9c/1e9c45d6fcf2fb48dc47756e4cb20174/0128931043v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/8b/42/8b4271e1bedea432ab03c83959e30431/0128818204v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/87/5a/875a8fa395c1eec9677e075fae7f5e8e/0128793884v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/93/2f9364112e8c6ff38c26f9ba34d0f692/0128791306v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/30/cb30ebdca7fcaea281749cb396654eb3/0124716339v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0b/b4/0bb4cdfa862043eac04c6a195e59b3e0/0124131782v2.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/60/7e/607ec89d5d9b5/white-frame.jpg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/66/9a/669a2816c84be/pcim-logo.png)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/24/d2/24d291de6c9171095b9845a81aa2edf3/0124999171v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/0d/d0/0dd02f3d5a1c83c1be444f73910e6b30/0126472071v2.jpeg)