BATTREY SYSTEMS Power electronics in energy storage

Related Vendors

In the course of the energy transition, the storage of energy is a central issue. The core behind the idea of sector coupling is the efficient use of both electrical and chemically stored energy as well as the efficient use or reuse of waste heat. "Storing energy" therefore refers to both the storage of electrical and thermal energy.

This broad concept of energy storage is reflected in a range of practical solutions that are already being implemented today.

The paths currently being followed include

- Storage and direct utilization of thermal energy from waste heat, e.g. industrial processes

- Use of thermal energy from solar thermal systems

- Conversion of electrical energy into chemical substances, "power to gas" and the necessary production of hydrogen from electrolysis

- Direct storage of electrical energy in batteries

From power electronic applications’ point of view, the focus is clearly on systems that store electrical energy as directly as possible. The most efficient and currently fastest growing technology is storing energy in batteries. The greatest progress in the recent past has been made in the field of cell chemistry. Nevertheless, steps have also been taken in the field of power electronics.

Battery energy storage (BESS) systems are used to a large extent on a scale of several kWh as buffer storage for balcony power plants and PV systems in the private sector. In 2025, the installed capacity of these systems in Germany was around 4 GWh, and around 400,000 new battery storage systems were connected to the grid.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/e5/6ee5ad1dc45fd69a5a5718147605850a/0129347492v2.jpeg)

BATTERY STORAGE

MWh battery energy storage: Redefining modern power infrastructure

Such systems, usually with less than 15 kWh of storage, have power electronics that charge the batteries with 48-96 V and regulate the energy flow between the grid and the battery. Storage systems featuring battery packs with up to 400 V, as they are also used in electromobility, are currently complementing the market.

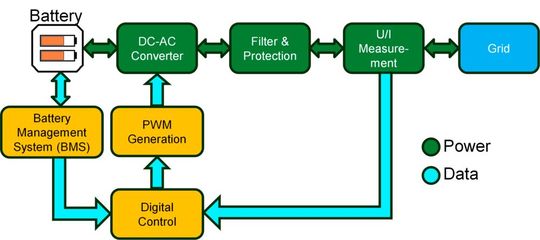

The power electronic structure is sketched as a block diagram in Figure 1.

For industrial purposes and the storage of energy in the MWh range modular structures are used for scalability reasons. Container-style solutions integrate battery storage, power- and monitoring electronics as well as thermal management.

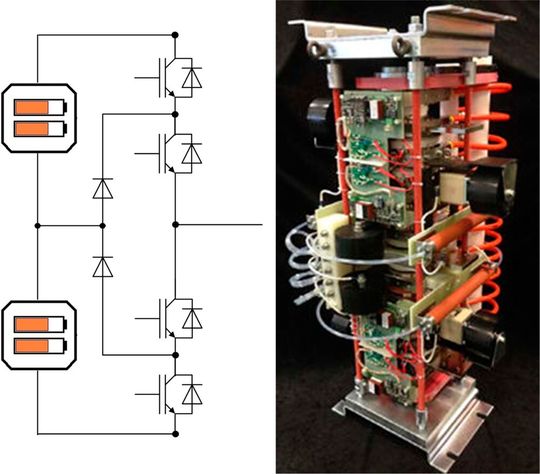

The basic structure remains the same while the higher currents and power levels require components with suitable key data. For the reliable operation of battery systems in the MW-range, solutions based on so-called disk devices get into focus. These are power electronic components that are optimized for the control of high currents and are assembled in stacks to form sub-assemblies.

Figure 2 depicts such a stack as it is used in high-power battery systems.

Due to the modularity of the approach, this can be scaled up easily. For example, MW/MWh systems can be expanded to virtually any power and capacity by connecting these container modules in parallel.

A commonality in all these approaches is, that the storage systems have so far been integrated into the low-voltage grid. However, for the distribution of energy on a large scale, it would be helpful to be able to feed energy directly into the medium-voltage grid.

Medium voltage is the voltage level from 1500 to 30,000 volts. Batteries have so far been integrated here with the help of medium-voltage transformers, which, however, has some disadvantages:

- 1. the transformer requires a considerable installation space,

- 2. it causes costs that could be avoided and

- 3. it generates undesirable power losses.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/62/80/6280da00d591873bf8f0b2a70e5986e0/0129064771v4.jpeg)

POWER SEMICONDUCTOR

High-efficiency IGBT series targets solar and energy storage systems

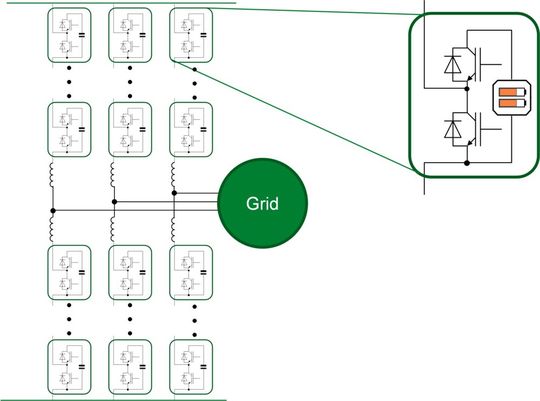

One way to connect batteries directly to the medium-voltage grid is to connect individual battery packs in series as part of a multilevel converter. With battery packs of 96 V, energy can be fed directly into a 10 kV medium-voltage network using 150 packages in series.

What at first sounds like a foolishly high effort becomes more important when taking a closer look.

When fed in at 10kV, the current to transmit 1 MW is only 57 A. To feed the same power into the 400V-Net, currents of over 1400A would be required. This alone could reduce the amount of copper required by as much as 97%.

In the outlined approach, the semiconductors do not need to operate at high frequency, which reduces switching losses. In addition, inexpensive semiconductors with low blocking voltages and thus low static losses are used, both of which increases the efficiency of the system.

A schematical overview of the structure is given in Figure 3.

The highly modular design would be easy to maintain and can be set up with little effort in a so-called n+1 redundancy, which means that the failure of a single part of the power electronics would not result in the failure of the entire system.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/images.vogel.de/vogelonline/bdb/1783100/1783113/original.jpg)

Conclusion:

The energy transition cannot succeed without storage. The storage of otherwise unused energy, generated from fluctuating renewable sources, holds enormous potential that should be used at all levels of supply.

Sector coupling with simultaneous consideration of electrical and thermal energy is gaining in importance, as is the storage of electrical energy in batteries.

For the wide range of conceivable solutions in this field of applications, the market offers semiconductor components that support the construction of systems in the range of a few kW/kWh as well as the creation of large-scale storage systems reaching and exceeding MW/MWh.

(ID:50710087)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/7d/b4/7db4fc5b8cd18e6eb2c864a3c329f177/0129545524v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/f5/d2/f5d2bce7c01775fe62d4c6ecebc8c5ba/0129188745v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/38/cb38bf951c0af8a8de423fedce2489d8/0129352475v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b8/13/b8139abf82c98aa04248a4a119d28c13/0129194616v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/60/40/6040b2e00aef20b4f9d92e8ac9f79c32/0129349725v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b3/13/b313941dbf7adc57c6d144966106d82b/0129219607v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/56/a4/56a4d9b6ee131a7a00b8b89dabf108f9/0128979281v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3e/99/3e997b758543c9a581667cee711b6938/0129540100v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/fd/6efdf487345688ca2b71ae23a398bc5f/0128553399v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/f0/ccf0b07809eaa14635374ad332fd7ea3/0129431466v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/8a/d5/8ad5fce4f456b8cd4507598c6c3d92c8/0129546435v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/30/cb30ebdca7fcaea281749cb396654eb3/0124716339v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/thumbor.vogel.de/945pzb0o80T2RjQQYBgLdszhUts=/500x500/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/67/50/67503e4ee8acf/headshot-schulz.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/60/7e/607ec89d5d9b5/white-frame.jpg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/68/2c/682c3e2e9a195/logotype-rvb.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/e5/6ee5ad1dc45fd69a5a5718147605850a/0129347492v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/94/54/94548eaecd020681e558d563bc48ba1d/0128926221v2.jpeg)