E-WASTE Global overview of e-waste, WEEE, EPR, and PCF

Related Vendors

In the face of rapidly increasing e-waste due to technological advancements, this article delves into global management strategies, focusing on WEEE, EPR, and PCF. It highlights the environmental impacts, emerging waste streams, and the necessity for cohesive policies to address the escalating e-waste challenge effectively.

E-waste is any discarded product containing electrical or electronic components that requires electricity or electromagnetic fields to function. It is the fastest-growing waste stream globally, rising at ~3 % annually [UNITAR, 2024].

Toxic components in current w-waste

Today’s e-waste contains numerous hazardous substances:

- Heavy metals: Lead in solder and CRT glass, mercury in switches and backlights, cadmium in batteries, arsenic in semiconductors [UNEP, 2019].

- Persistent organic pollutants (POPs): Brominated flame retardants in casings, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in capacitors, and dioxins from uncontrolled burning [UNEP, 2020].

- Other toxics: Beryllium in connectors, selenium in photocells, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in refrigeration units.

Emerging and future high-impact e-waste streams

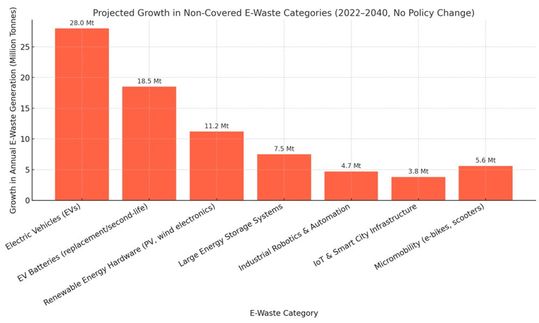

The electrification of transport, renewable energy, and industrial automation is set to introduce new and potentially more complex waste streams:

- Electric vehicles (EVs): Passenger cars, buses, trucks — high-capacity lithium-ion batteries, rare earth magnets, high-voltage systems.

- Electric two-wheelers & micromobility: E-bikes, scooters, mopeds — short product life cycles, non-modular battery designs.

- Autonomous & connected vehicles: Sensor arrays (LIDAR, radar), onboard AI processors, telematics hardware.

- Renewable energy hardware: End-of-life PV modules, wind turbine control systems, inverters.

- Energy storage systems: Residential and grid-scale battery banks.

- Industrial robotics & IoT: Smart city infrastructure, environmental sensors, industrial automation.

If production trends hold, these categories could add 20–26 million tonnes of additional annual e-waste by 2030 and 60–75 million tonnes by 2040, on top of existing flows [UNITAR, 2024; IEA, 2023].

Global e-waste growth outlook

As we look at the global e-waste growth outlook, baseline projections indicate a significant increase in electronic waste over the coming decades, underscoring the urgent need for effective management strategies and regulatory measures.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/8d/3d/8d3d8943c4ea211a64cabb24f7404944/0125827250v2.jpeg)

CLIMATE NEUTRAL

The EU Green Deal and the electronics sector: A strategic imperative for circularity

Baseline projections

Global e-waste reached 62 Mt in 2022 and is expected to hit 82 Mt by 2030 under current conditions [UNITAR, 2024].

| Year | Baseline projection | Additional from emerging categories | Total projected |

| 2030 | 82 Mt | +20–26 Mt | 102–108 Mt |

| 2040 | 100 Mt | +60–75 Mt | 160–175 Mt |

Current e-waste flow to Africa

Roughly 1.3 million tonnes of used electrical and electronic equipment (UEEE) enter Africa every year, of which 35–40 % is non-functional upon arrival and therefore qualifies as e-waste [Baldé et al., 2017; UNU, 2020].

- Nigeria receives around 500,000 tonnes/year, mainly via the Port of Lagos. An estimated 150,000–200,000 tonnes of this is pure e-waste, despite being declared as reusable goods [UNEP, 2018].

- Ghana imports about 215,000 tonnes/year, with 65,000–85,000 tonnes arriving in non-functional condition. Much of this is processed in informal recycling hubs such as Agbogbloshie, where dismantling often involves open burning of cables and acid leaching of circuit boards to recover metals [BAN, 2019].

Environmental and health impact:

- Lead levels in soil around Agbogbloshie have been recorded at more than 100 times WHO safety thresholds [UNEP, 2018].

- Acid baths used for metal recovery release toxic effluents into water sources, contaminating fishing grounds and agricultural areas.

- Workers, often teenagers, inhale fumes from burning PVC insulation and are exposed to persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like brominated flame retardants.

The Basel Convention challenge:

The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (in force since 1992) is intended to prevent the shipment of hazardous waste — including e-waste — to countries lacking environmentally sound management capacity. However, significant loopholes exist:

- Classification as “used goods” – Functional second-hand electronics are legally tradable; exporters often declare near-waste items as “for reuse” to circumvent restrictions.

- Inconsistent national enforcement – Customs inspections and testing protocols vary, making it easy to pass off e-waste as functioning equipment.

- Lack of explicit coverage for emerging waste categories – Large lithium-ion batteries, EV components, and solar panels are not always clearly listed as hazardous, creating grey areas for export.

As a result, substantial volumes of non-functional electronics continue to flow into African markets, where they enter the informal recycling sector under unsafe conditions. Addressing these loopholes — through clearer definitions, mandatory functionality testing, and harmonised enforcement — is considered critical by many environmental agencies [UNEP, 2019; BAN, 2019].

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/61/09/6109228bdc722/kampagnenbild-webkon-pb-20210831.jpeg)

WEB CONFERENCE: THE FUTURE OF ENERGY

Renewable energies – chances & challenges for a clean future

EPR, WEEE, PCF, and GHG – A connected policy framework

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is the overarching policy principle making producers financially and/or operationally responsible for end-of-life management of their products [OECD, 2016].

WEEE (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive) in the EU is a direct implementation of EPR for electronics [EC, 2023]. It sets binding collection and recycling targets (e.g., 65 % of average product weight placed on the market in the last three years) and requires producers to finance take-back schemes. The EU WEEE Directive is widely considered a benchmark due to its comprehensive scope, measurable targets, and harmonised enforcement across 27 Member States [UNEP, 2019].

PCF (Producer Compliance Fee) is a financing mechanism under EPR, allowing producers to pay into collective schemes instead of arranging their own take-back.

PCF (Product Carbon Footprint) is the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of a product, expressed in CO2₂-equivalents (CO2e), covering its full life cycle [ISO 14067:2018].

Why CO₂ as the reference unit?

- Largest share of anthropogenic GHG emissions (~76 % of total) [IPCC, 2021].

- Other gases (CH4, N2O, HFCs) are standardised into CO2e via Global Warming Potentials (GWPs), enabling comparability.

- Aligns with Paris Agreement targets and most corporate carbon disclosure frameworks.

Linking EPR-based PCFs with carbon PCFs ensures e-waste regulation also supports climate change mitigation.

Global e-waste regulation coverage (including EU)

The following table provides a comprehensive overview of the current status of global e-waste regulations, highlighting the presence of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and other key initiatives across various regions and countries.

| Region | Country/Territory | Status | EPR Present? | Scope & Targets | Emerging Waste Coverage* | Annual E-Waste Contribution (2022, est.) |

| EU | EU-27 aggregate | Enacted | Yes | WEEE Directive 2012/19/EU; 65% collection target | No | ~12 Mt |

| Other Europe | Norway | Enacted | Yes | WEEE-aligned EPR | Partial (batteries, EV pilots) | ~0.14 Mt |

| Switzerland | Enacted | Yes | ORDEE & SWICO systems | Partial (PV panels, batteries) | ~0.25 Mt |

|

| UK | Enacted | Yes | WEEE Regulations 2013 | No | ~1.6 Mt |

|

| North America | USA | Enacted (state-level) | Yes (25+ states) | State-specific take-back | No | ~6.9 Mt |

| Canada | Enacted (provincial) | Yes | Province-specific targets | No | ~0.73 Mt |

|

| Latin America | Brazil | Enacted | Yes | Reverse logistics | Partial (batteries) | ~2.1 Mt |

| Chile | Enacted | Yes | Priority products targets | No | ~0.21 Mt |

|

| Colombia | Enacted | Yes | IT take-back | No | ~0.15 Mt |

|

| Argentina | Partial | Partial | Provincial/local only | No | ~0.45 Mt |

|

| Asia–Pacific | China | Enacted | Yes | Subsidised recycling, import ban | No | ~11.6 Mt |

| Japan | Enacted | Yes | Home Appliance & Small WEEE | Partial (EV battery pilots) | ~2.57 Mt |

|

| South Korea | Enacted | Yes | EPR since 2003 | Partial (EV batteries) | ~1.07 Mt |

|

| India | Enacted | Yes | E-Waste Rules | No | ~2.0 Mt |

|

| Singapore | Enacted | Yes | Resource Sustainability Act | No | ~0.07 Mt |

|

| Australia | Enacted | Yes | NTCRS | No | ~0.55 Mt |

|

| Indonesia | Enacted | Yes | National Action Plan | No | ~1.6 Mt |

|

| Lao PDR | Enacted | Yes | Solid Waste Strategy | No | Negl. |

|

| Thailand | Enacted | Yes | E-Waste Plan | No | ~0.5 Mt |

|

| Vietnam | Enacted | Yes | E-Waste Plan | No | ~0.4 Mt |

|

| Middle East | UAE | Enacted | Yes | Federal Law No. 12/2018 | No | ~0.26 Mt |

| Israel | Enacted | Yes | E-Waste Law 2014 | No | ~0.17 Mt |

|

| Africa | South Africa | Enacted | Yes | Waste Act (2021) | No | ~0.35 Mt |

| Madagascar | Draft | Planned | Draft policy | No | Negl. |

|

| Kenya | Draft | Planned | Draft Regulations 2013 | No | ~0.02 Mt |

|

| Ghana | Draft | Planned | E-Waste Control Act | No | ~0.04 Mt |

|

| Nigeria | Draft | Planned | National Environmental Regs | No | ~0.35 Mt |

|

| Eastern Europe & Central Asia | Georgia | Enacted | Yes | WEEE law | No | ~0.03 Mt |

| Moldova | Enacted | Yes | WEEE law | No | ~0.02 Mt |

|

| Ukraine | Enacted | Yes | WEEE law | No | ~0.3 Mt |

|

| Belarus | Enacted | Yes | EPR under waste law | No | ~0.2 Mt |

|

| Russia | Enacted | Yes | EPR under waste law | No | ~1.6 Mt |

|

| Kazakhstan | Enacted | Yes | EPR under waste law | No | ~0.12 Mt |

|

*Emerging Waste Coverage = whether EVs, renewable energy hardware, or large batteries are explicitly in scope.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5f/fe/5ffedb2e0ffa6/listing.jpg)

Conclusions and policy outlook

As we assess the future of electronic waste management and policy development, several key considerations and action points must be addressed to effectively tackle the growing global e-waste challenge.

- Without urgent expansion of scope to emerging waste streams, global e-waste could reach 160–175 Mt/year by 2040.

- The EU WEEE Directive remains the benchmark for structured EPR implementation but lacks explicit provisions for future electronics categories.

- The Basel Convention, while designed to restrict transboundary hazardous waste movements, has loopholes — notably the classification of e-waste as “used goods” — which enable continued exports to Africa [BAN, 2019].

- Integrating Producer Compliance Fees with Product Carbon Footprint reporting could bridge waste regulation and climate goals.

- Investment is urgently needed in safe recycling infrastructure, especially in Africa, to eliminate hazardous informal practices.

References

- BAN (Basel Action Network) (2019). Exporting Harm: The High-Tech Trashing of Africa. BAN Report.

- Baldé, C.P., Forti, V., Gray, V., Kuehr, R., Stegmann, P. (2017). The Global E-waste Monitor 2017. United Nations University (UNU).

- EC (European Commission) (2023). Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). Brussels.

- IEA (International Energy Agency) (2023). Global EV Outlook 2023. Paris: IEA.

- IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ISO (2018). ISO 14067:2018 Greenhouse gases — Carbon footprint of products — Requirements and guidelines for quantification.

- OECD (2016). Extended Producer Responsibility: Updated Guidance. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- UNEP (2018). A New Circular Vision for Electronics. United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP (2019). Technical Guidelines on E-Waste. Basel Convention.

- UNEP (2020). POPs and E-Waste. Basel Convention Factsheet.

- UNU (United Nations University) (2020). E-waste in West Africa: Policy and Practice.

(ID:50526679)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/thumbor.vogel.de/f3g2ouosszYDI6Qcyea5EqIzON0=/500x500/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/68/83/6883a88b8c321/ole-gerkensmeyer.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/67/e2/67e2a1ef13aba/logo-ab-rgb-1.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/62/b9/62b980cddf5d6/ceramtec.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/63/c7/63c7da97be945/diotec.png)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3f/8a/3f8a509fe74fbd8f221e9a0530516b64/0126938143v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3a/fb/3afbb164d08101045248130293a340b7/0126044396v2.jpeg)