POWER CONVERTER Compensating a Flyback Converter

Related Vendors

The flyback converter is a popular switching structure found in consumer appliances but also in industrial products. Either used as a main converter or as an auxiliary power supply, it can be supplied from a low- or high voltage dc rail. The converter is simple to build with its single switching transistor and lends itself well to producing cost-effective power supplies from a few watts to 100-150 W roughly.

Despite its simplicity of design, the converter still needs to be properly controlled for the best-possible dynamic performance, regardless of the grid input voltage or the output current. Many engineers ignore the design methodology for determining the right compensation network for their project and often resort to trial-and-error for stabilizing their converter. If this approach can work for a quick assessment, it cannot guaranty stability margins for long-term reliability. This short article shows how simulation can assist you in characterizing the dynamic response of a converter, to further compensate it for adequate performance in closed-loop operation.

Characterizing the Power Stage

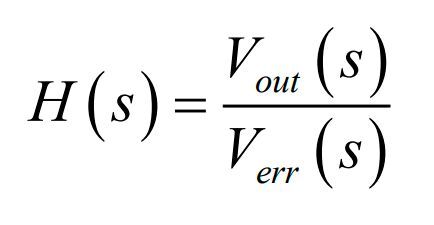

Any loop stabilization exercise starts with the small-signal transfer function of the process you want to control. It is the power stage of a switching converter, which converts energy from the dc rail to power the load, that we want to characterize in frequency. If we excite the control variable of this converter – e.g., the inductor peak current îL in current-mode control or the duty ratio D in a voltage-mode control version – how does this stimulus propagate through the circuitry to deliver a response observable on the output? The complex mathematical relationship linking the stimulus to the response is called the control-to-output transfer function which I arbitrarily designated as H (see equation 1).

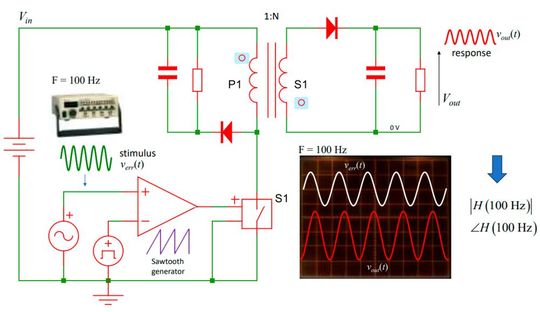

In this expression, Verr represents the error voltage delivered by the compensation network which is later on converted into a peak current or a duty ratio setpoint. Vout designates the output voltage of the converter which conveys the ac response we need. Figure 1 illustrates the basic concept applied to a simplified flyback converter in this particular example.

A modulation voltage of sufficiently-low amplitude is applied to the converter whose dc operating point is ensured by adequate biasing conditions. The input and output signals can be visualized on an oscilloscope to check the system remains linear during the ac sweep – for instance between 10 Hz and 100 kHz – but since you want to evaluate the magnitude and the phase of the transfer function point by point, the best is to resort to a frequency-response analyzer (FRA) which is specialized in this type of automated acquisition.

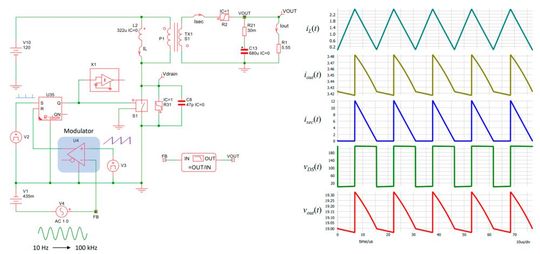

Simulating the Circuit with SIMPLIS

Building a prototype to run frequency measurements is a mandatory step of any serious development cycle. However, it is possible to speed up the loop stabilization process by resorting to a simulation model run on a computer. When components parasitics are well extracted and reflected to the simulation template, then the simulated results are likely to closely match what the FRA will return. Therefore, it becomes possible to think of a potential compensation strategy on the computer prior to testing it on the bench, naturally saving a tremendous amount of time. Figure 2 depicts the simplest possible test setup to extract the control-to-output transfer function of a voltage-mode-controlled flyback converter. In this example, there is no return loop and a dc bias source on the control pin is necessary to set operating conditions.

The first thing to verify is the dc operating point, confirming the converter delivers its nominal voltage and current from the given input voltage. It is a mandatory sanity check to be sure the circuit operates as expected. Here, we wanted a 19-V output voltage with a 3.4-A current and this what the program confirms through the right-side waveforms. The dc bias V1 in series with the stimulus sets the right duty ratio while ac source V4 injects the modulation signal. The SIMPLIS algorithm will automatically size the ac injection amplitude to keep the system linear while extracting the modulated results comfortably from switching noise in the response, Vout.

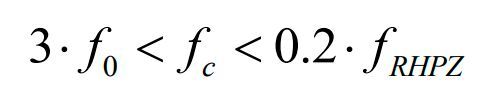

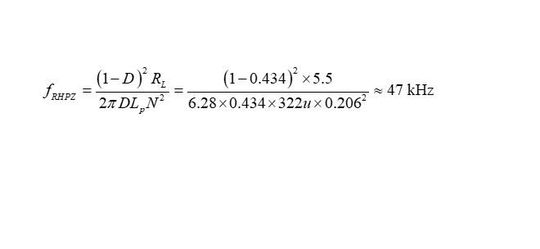

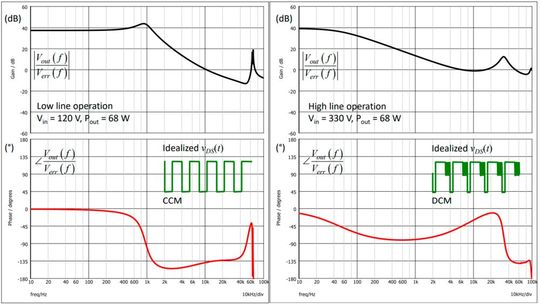

Figure 3 shows the ac response in the two possible operating modes, discontinuous conduction mode (DCM) and continuous conduction mode (CCM) when the converter is respectively biased from a 120- or 330-V dc rail. The dc bias in V1 is thus manually adjusted at 435 mV (Vin = 120 V) and 160 mV (Vin = 330 V) for a 19-V/3.5-A output.The ac response in CCM is that of a damped second-order circuit featuring two poles at resonance (ƒ0≈950 Hz) and a right-half-plane zero (RHPZ) typical of this type of converter. The crossover frequency ƒc must thus be selected above the resonance to make sure the loop has gain at this frequency but is reduced well below the RHPZ lowest position to prevent excessive phase lag at ƒc. The following guideline can be adopted in the process of selecting a possible crossover frequency (see equation 2).

In the given example, considering the components values, the low-line full-load RHPZ in CCM is evaluated at the frequency seen in equation 3.

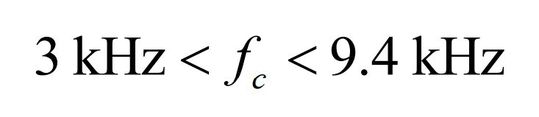

From this calculation, it is therefore possible to select a crossover frequency located between these limits (see equation 4).

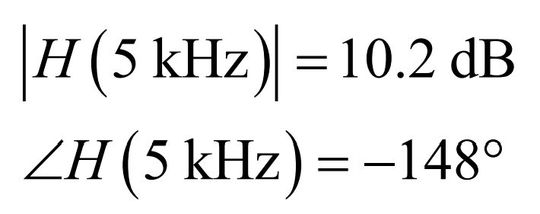

We can choose 5 kHz as a target and we simply read the CCM Bode plot from Figure 3 to extract the magnitude and phase at this frequency (see equation 5).

To crossover at 5 kHz, we need to design an active filter – the compensator – offering an attenuation of 10.2 dB at 5 kHz with a boost in phase of 128°, if we set 70° as a goal for the phase margin.

In DCM, the system is still a 2nd-order network but over-damped, with a dominant low-frequency pole. The phase lag approaches 90° and dips further down at high frequencies, considering the second pole and the RHPZ pushed to higher frequencies than in CCM. The compensation will thus be done in CCM, leading to a lower crossover in DCM conditions. That that respect, current-mode control offers better performance with an almost constant crossover point during mode transitions.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5f/fe/5ffedb2e0ffa6/listing.jpg)

Designing the Compensator

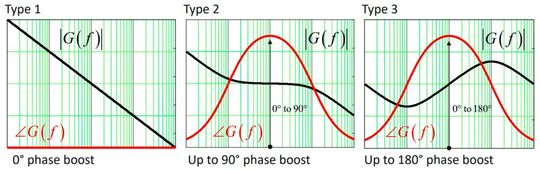

There are several normalized structures to choose from depending on the needed phase boost. Their dynamic responses appear in Figure 4. They are built around an operational amplifier (op-amp) but can also be implemented with a TL431, a shunt regulator or a transconductance amplifier (OTA). Design equations between theses solutions differ and are detailed in this book. Each of these compensators includes a pole at the origin, bringing a high gain at dc, for s = 0. Type 1 is a simple integrator, suitable in cases when no phase boost is necessary. Type 2, in addition to the integrator, brings a pole-zero pair which lets you adjust the phase boost from 0 to 90°. Finally, the type 3 adds another pole-zero pair to type 2 and represents a filtered PID with an additional high-frequency pole. The phase boost can peak up to a theoretical 180°.

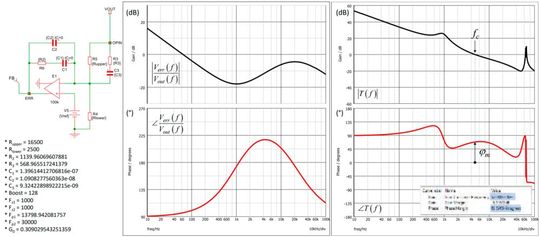

In our example, considering the needed phase boost of 128°, a type 3 built around an operational amplifier is what we will select. The components values are calculated by a macro as shown in Figure 5 and let you explore different compensation scenarios. In this approach, we placed two zeroes at the resonant frequency and a pole at half the switching frequency for rolling-off the gain and building margin. The second pole will be adjusted by calculation to match the phase margin budget of 70° that we have selected.

The compensated gain appears in the right-side of Figure 5 and confirms a crossover of 5 kHz with a good phase margin. The right-side peaking is an artefact located at the switching frequency of 65 kHz. The circuit must now be tested when it transitions to DCM and will certainly require a change in the strategy to ensure stability in DCM also. Please note that many of these switching converters can be freely downloaded from the author webpage and be run from the demonstration version Elements.

Conclusion

The starting point for stabilizing a switching converter is the determination of its power stage ac response. It is described by the control-to-output transfer function which indicates how a stimulus applied to the control pin, propagates in the circuit to form an observable response. The magnitude and phase response of the transfer function are then graphed on a Bode plot and data are extracted for compensation purposes. A specific compensation structure is selected to shape the loop response, providing reaction speed with adequate margins. The process is not that complicated and the possibility to simulate the converter with a dedicated package clearly provides additional help.

Would you like do dive deeper into the topic? Than have a look at Christophe Basso's newly released book "An Intuitive Guide to Compensating Switching Power Supplies".

Power Electronics in the Energy Transition

The parameters for energy transition and climate protection solutions span education, research, industry, and society. In the new episode of "Sound On. Power On.", Frank Osterwald of the Society for Energy and Climate Protection Schleswig‐Holstein talks about the holistic guidance his organization can provide.

Listen now!

(ID:50085561)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/thumbor.vogel.de/mguFAwuAxCGw9kVi3c_k2-HNi5I=/500x500/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/66/74/667444027a724/tof1.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/63/c7/63c7da97be945/diotec.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/60/7e/607ec89d5d9b5/white-frame.jpg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/11/f6/11f623653dec4b1553be3f9e86c6bdf2/0124267609v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b0/ef/b0ef0ff0d070954c6d09418740c6242a/0123681509v2.jpeg)