BASIC KNOWLEDGE Understanding TRIACs: The key to efficient AC power control in modern electronics

Related Vendors

After silicon-controlled rectifiers (SCRs), TRIACs are the most popular thyristors used in commercial AC power applications. This article explains TRIACs and their symbol, structure, operation, advantages, disadvantages, and applications.

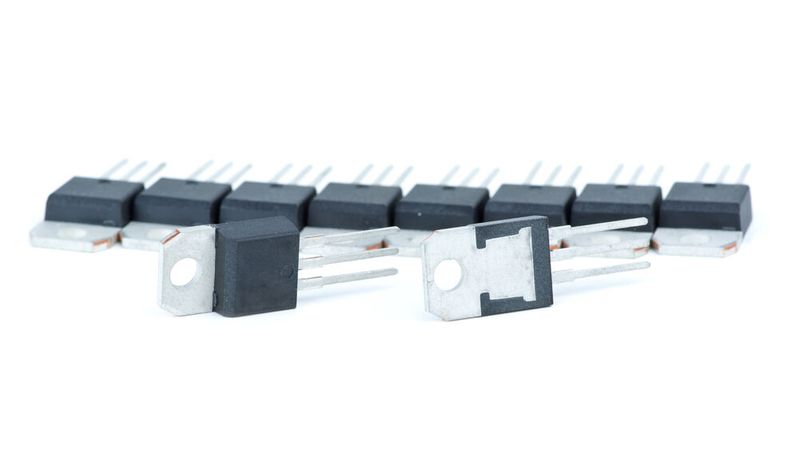

In 1958, engineers at General Electric filed a patent for a semiconductor device that would offer the capabilities of two thyristors in a single package. Little did the makers know that despite the trademark, the term “TRIAC” would become its official name. Today, after SCRs, TRIACs are the second-most popular devices among thyristors, making up a growing two-hundred-million-dollar industry.

Definition

TRIAC “Triode For Alternating Current” is a three-terminal bidirectional AC switch. It is a type of thyristor that can be triggered by either positive or negative pulse to the gate. TRIACs were developed for enhanced AC power control.

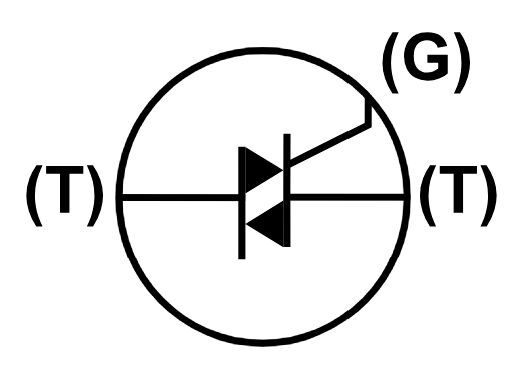

TRIAC symbol

The TRIAC symbol resembles two SCRs connected in an antiparallel configuration with a common gate terminal. The TRIAC symbol shows its three terminals: gate, main terminal 1 (MT1), and main terminal 2 (MT2).

The TRIAC symbol shows MT1 and MT2 instead of anode and cathode because TRIACs are bidirectional. Neither terminal is designated anode or cathode.

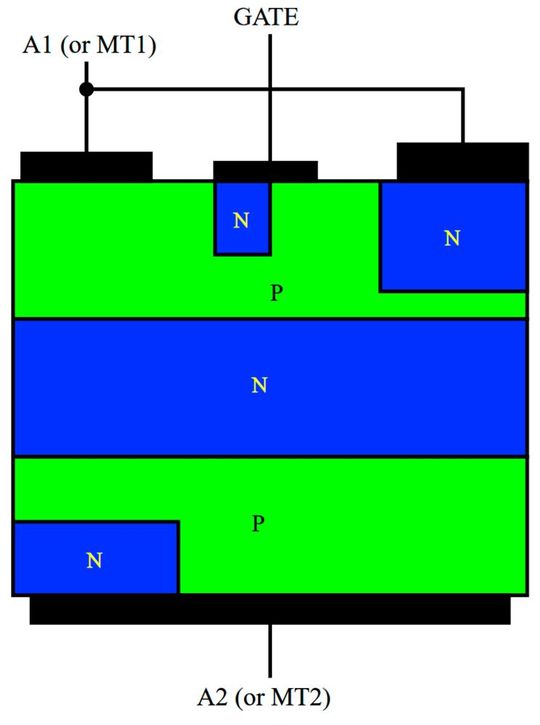

TRIAC structure

TRIAC is a three-layer structure that consists of three additional doped N regions. In simple words, TRIACs exhibit a six-region NPNPN structure. Each terminal is bilaterally connected to both N and P regions.

The TRIAC structure forms two internal thyristor paths that can conduct in both directions.

TRIAC working principles

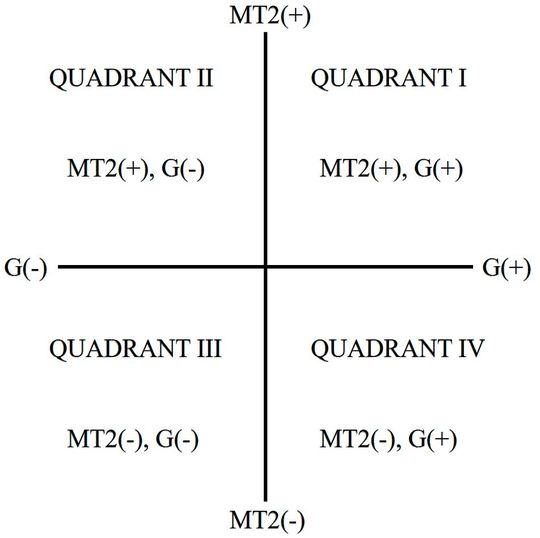

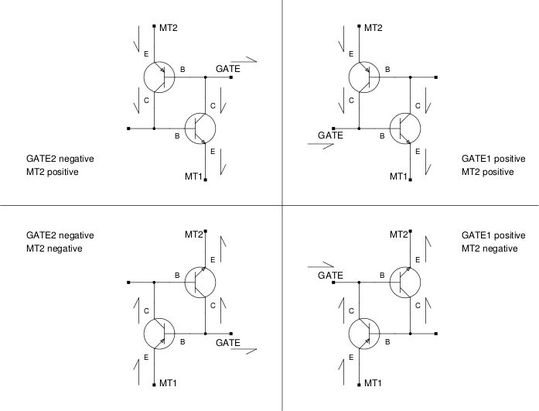

Unlike other thyristors, primarily SCRs, TRIACs can operate through negative or positive gate pulses. Hence, TRIACs can function in all operating modes of their characteristic curves, whereas SCRs operate only in two quadrants, requiring a positive gate pulse for triggering.

The polarities of MT2 and the gate are graphically marked. In mathematics, each graph is segregated into four regions called quadrants. TRIACs can conduct current when MT2 is either positive or negative, and the gate is triggered through either a positive or negative pulse.

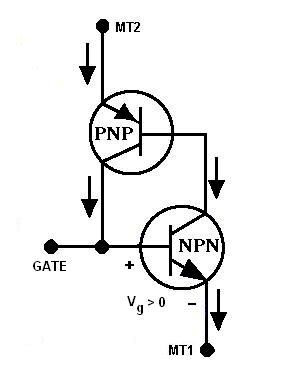

Just like other thyristors, alternating PN layers form two transistors- PNP and NPN. These internal transistors have both of their base terminals connected.

The gate threshold current is the minimum current required to turn on the relevant junctions or internal transistors. The value of the gate threshold current depends upon the temperature and voltage across MT1 and MT2. It is generally in the order of a few milliamperes.

TRIAC sensitivity decreases down the quadrant.

Sensitivity = Q1 > Q2 > Q3 > Q4

Quadrant 1 requires a lesser gate current to turn on the TRIAC, whereas quadrant 4 needs more.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5f/fe/5ffedb2e0ffa6/listing.jpg)

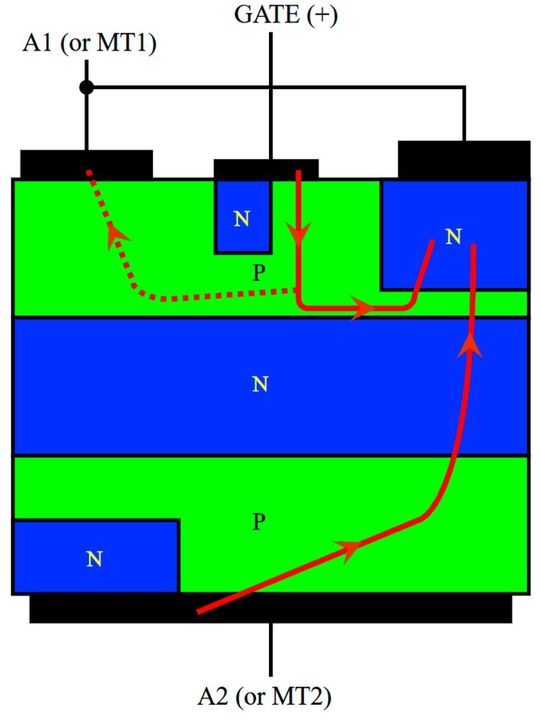

Quadrant 1: Positive MT2 and positive gate

In quadrant 1, MT2 and gate are both positive with respect to MT1. When a positive pulse is applied across the gate, some portion of the gate current leaks into the p-type layer near the MT1. Image 5 depicts this current through a dotted line. It happens because the current tends to follow the easiest ohmic path without participating in any triggering process.

The leaking current injects holes into the highly resistive p-layer. The stacked N, P, and N layers beneath MT1 behave like an NPN transistor. The rest of the current enters the base of the NPN transistor. The NPN transistor turns on. The NPN transistor draws current from the base of the PNP transistor— turning it on.

Once NPN and PNP transistors are active, the TRIAC starts to conduct current. It enters the latching state– typical thyristor behavior. The current flows from the positive MT2 terminal to the TRIAC structure, eventually to the MT1. TRIACs are more sensitive when MT2 and gate are both positive with respect to MT1 in quadrant 1. The reason for increased sensitivity in the first quadrant operation is suitable charge carrier injection and less effort to trigger the latching operation.

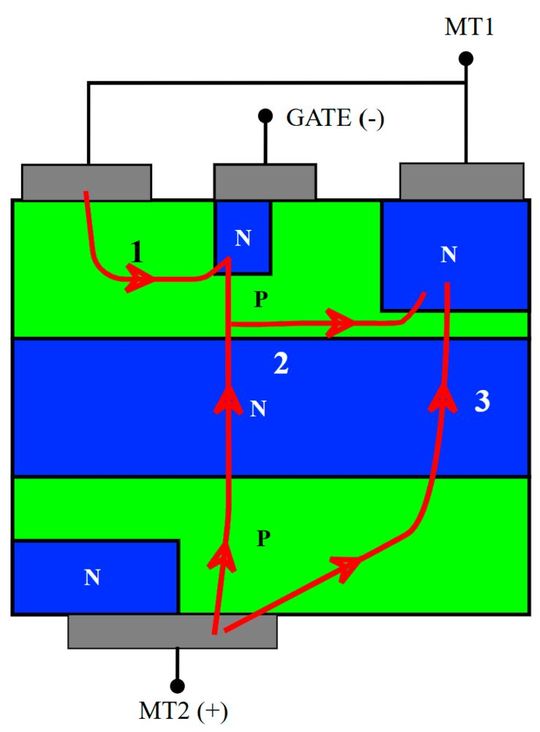

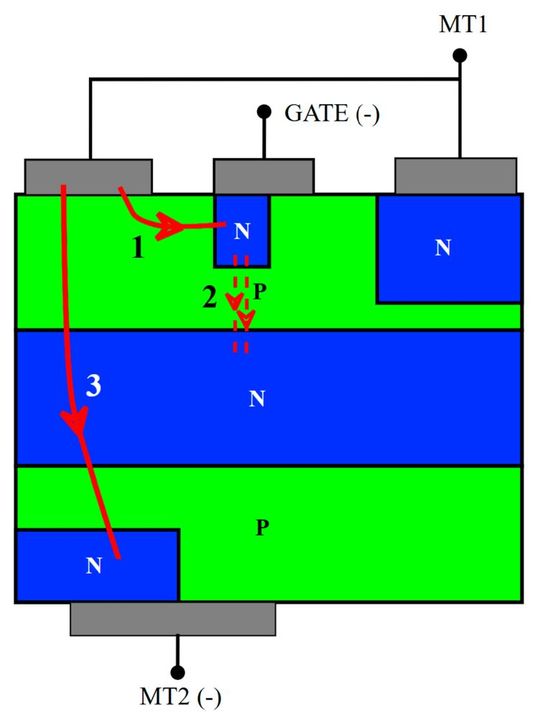

Quadrant 2: Positive MT2 and negative gate

In quadrant 2, MT2 is positive, but the gate is negative with respect to MT1. Both MT1 and gate are negative. However, the gate is more negative compared to MT1. As a result, the current from MT1 flows through the PN junction into the gate. The point marked by point “1” in image 7 shows a small combination of NPN and PNP transistors.

At this point, the gate acts like a cathode. The current flow initially turns on this combination. The point marked by point “2” in image 7 shows that the voltage difference in the p-layer near the gate increases towards MT1. The voltage difference between the gate and MT2 is less than the newly formed voltage difference (between the gate and MT1). As a result, current flows laterally in the device.

The lateral current flows from left to right in the p-layer. It helps to turn on the NPN transistor formed under MT1. As a consequence, the PNP transistor from MT2 to the upper p-type layer (near the gate) turns on. Once both transistors turn on, the TRIAC latches on to the conduction state. In image 7, point “3” showcases the action of current flow from MT2 to MT1, throughout the TRIAC structure, including the lateral current flow.

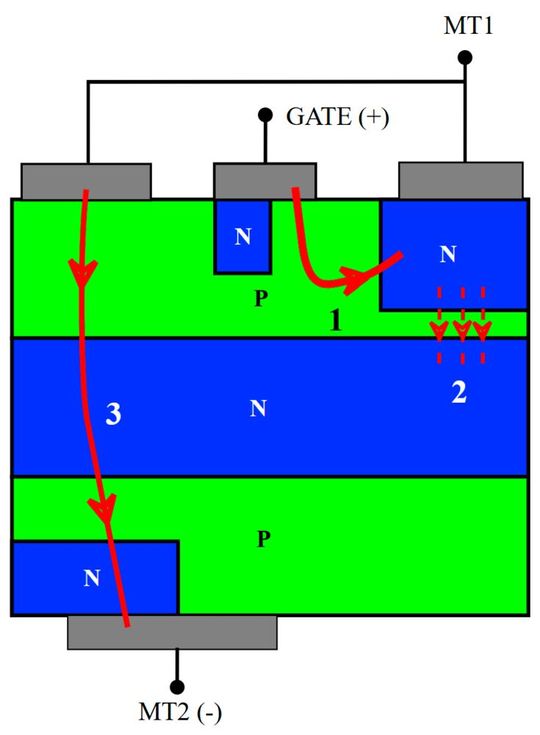

Quadrant 3: Negative MT2 and negative gate

In quadrant 3, MT2 and gate are both negative with respect to MT1. Due to polarities, the PN junction between MT1 and the gate becomes forward-biased. It is shown by the point “1” in image 8. Some electrons do not recombine and get injected into the n-layer, as shown across point “2” in image 8. The p-layer acts as the emitter of the PNP transistor.

Once electrons enter the n-layer, the overall voltage of the n-layer decreases. In simple words, the region becomes more negative. The n-layers function like the base of the PNP transistor. The base becomes negative for the emitter to conduct. Hence, the PNP transistor turns on. The process where transistor PNP is turned on by lowering base potential, instead of applying a pulse, is called remote gate control.

The lower p-layer, beneath the n-layer, witnesses an increase in its voltage. This is due to the injection of electrons in the n-layer. As a result, the base becomes negative. The lower p-layer functions to be the collector of the PNP transistor and the base of the NPN transistor. As a result, the NPN transistor also turns on. The action is shown by point “3” in image 8. The current flows from MT1 to the TRIAC structure to MT2.

Quadrant 4: Negative MT2 and positive gate

In quadrant 4, MT2 is negative, but the gate is positive with respect to MT1. Due to polarities, current flows from the gate to MT1. Simply put, current flows from the p-layer near the gate to the n-region near MT1. It is shown by the point “1” in image 9. Free electrons, minority carriers, do not recombine and get injected into the p-layer.

The dotted line in the image shows those free electrons. The NP junction collects some of these free electrons, while the remaining ones enter the n-layer as shown across the point “2” in image 9. Once free electrons enter the n-layer, the overall voltage of the n-layer decreases, and it becomes more negative. The n-layer functions like the base of the PNP transistor. Similar to the quadrant 3 operation, the remote gate control turns on the PNP transistor.

The lower p-layer under the n-layer functions to be the collector of the PNP transistor and the base of the NPN transistor. As a result, the NPN transistor also turns on. The action is shown by point “3” in image 9. The current flows from MT1 to MT2 throughout the TRIAC structure. Quadrant 4 is the least sensitive because of the complex activation process and restrictive triggering conditions. Most TRIACs cannot operate in quadrant 4.

TRIAC turn off

Just like other thyristors, once a TRIAC starts to conduct current, it latches to the conduction state even if the gate pulse is removed. The current between MT1 and MT2 should be more than a critical value called “latching current” to keep the TRIAC on. Once the latching current reaches below a value called “holding current”, the TRIAC turns off. Both values are in the order of milliamperes.

TRIAC advantages

TRIACs offer compact, efficient, and safe solutions for power control, making them ideal for various high-voltage applications. The advantages include:

- TRIACs are smaller in size, requiring a single heat sink of a larger size for heat dissipation

- TRIACs need a single fuse for protection

- The TRIAC breakdown is safe

- TRIACs can be operated under high voltages (up to kV), making them suitable for power control applications

- Easily mounted on PCBs

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/49/41/49414aec54b828f2484e3bf80ad0634d/0100423163.jpeg)

PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARDS

What’s involved in the process of PCB design?

TRIAC disadvantages

Despite their utility, TRIACs may present challenges such as sensitivity to temperature fluctuations, accidental triggering, and limitations with high-current applications. Some specific disadvantages are:

- TRIAC is a current-controlled device

- At high temperatures, TRIACs face increased internal leakage

- TRIACs can be accidentally turned on due to the rapid voltage changes

- During the TRIAC turn-on process, a sharp increase in current can damage the device

- TRIACs are unsuitable for highly inductive or capacitive loads due to the presence of a small triggering current

- TRIACs require pulse trains, sometimes multiple pulses to turn on— a slow process

- Due to their bidirectional nature, TRIACs can be mistakenly triggered in either direction

- TRIACs have a lower dv/dt rating

- TRIACs are unreliable compared to other thyristors. They are unsuitable for high-current applications

TRIAC applications

From AC power control to automation systems, TRIACs serve a range of applications, providing versatile solutions for both domestic and industrial use. These applications cover:

- AC switches

- Power control in AC circuits

- Power amplification from low to medium voltages

- AC mains on-off switches in single-phase or three-phase systems

- High-power lamp switching

- Light dimmers to adjust the bulb

- Speed controllers in domestic electric fans and blenders

- The thermosetting temperature in heat controllers

- Speed controllers in industrial motors

- Automation controllers in homes and commercial buildings

- Single-phase motor starters

- Modern computerized PCBs in appliances

References

(ID:50426224)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/63/c7/63c7da97be945/diotec.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/60/7e/607ec89d5d9b5/white-frame.jpg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/21/7f/217fcc66cf062b3e3212dcb6c2d53992/0124480366v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/af/07/af073e302fcca1153bcaca553175006c/0124143921v2.jpeg)