BASIC KNOWLEDGE Thyristor: Definition, types, and more

Related Vendors

Just like power transistors and power diodes, thyristors are another important type of power semiconductor device. Thyristors are among the largest and heaviest semiconductor devices that can handle large amounts of power, something that transistors cannot do. The article talks about thyristors in detail, including their construction, types, operation, advantages, and disadvantages.

What is a Thyristor?

The concept of thyristors emerged during the discovery of the negative resistance effect. Around the 1950s, researchers at Bell Labs were exploring ways to develop a latching semiconductor switch. A group of power engineers at General Electric ended up developing the world’s first thyristor in 1956. The name “Thyristor” came up from a combination of “Transistor” and “Thyratron”. Thyratron is a historic gas-filled tube that performs a similar function.

Definition thyristor

A thyristor is an active four-layer current-controlled power semiconductor device used to control a large amount of power. They are partially controllable bistable switches, operating in either off (0) or on (1) states. Simply put, thyristors can either remain on or off; there is no in-between.

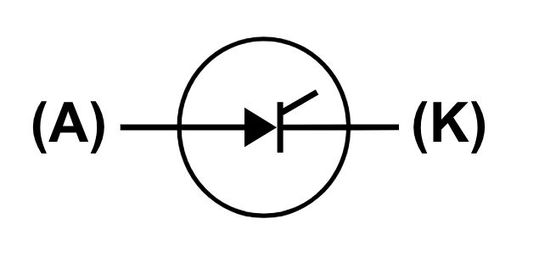

Thyristor symbol

The symbol of the thyristor showcases its three terminals: Anode (A), Cathode (K), and Gate (G). The anode and cathode terminals are connected in series with the load to control the power.

The cathode and anode terminals handle large applied voltages and conduct major currents through the thyristor. The gate terminal is the control terminal that enables performing controlling and switching operations.

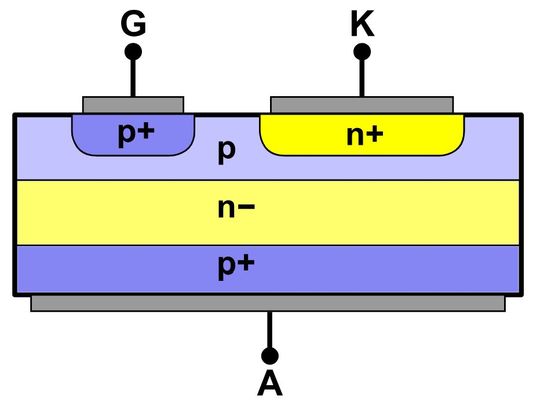

Thyristor construction

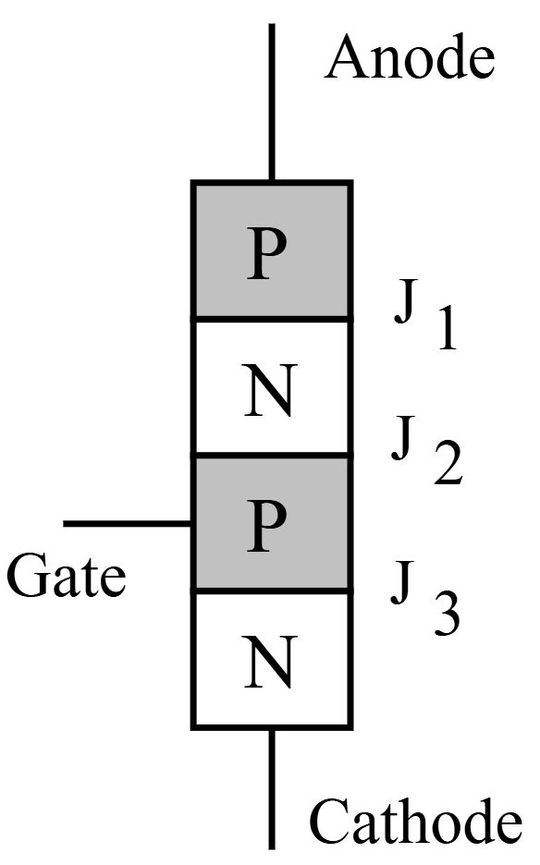

A thyristor is made from an alternating layer of P and N-type semiconductors. It consists of two heavily doped P and N layers, separated by a lightly doped N layer and a moderately doped P layer.

PNPN: P (heavily doped) — N (lightly doped) — P (moderately doped) — N (heavily doped)

Anode is placed at the heavily doped P layer. Similarly, the cathode is placed at the heavily doped N layer. The gate is attached to the moderately doped P layer near the cathode.

A thyristor consists of three PN junctions in series.

- Junction J1: Heavily doped P layer and lightly doped N layer.

- Junction J2: Lightly doped N layer and moderately doped P layer.

- Junction J3: Moderately doped P layer and heavily doped N layer.

The lightly doped n-region is a highly resistive region of the thyristor. Having junction J2 inside, the lightly-doped n-region is the most critical part of the thyristor that supports conducting capabilities. To improve forward voltage ratings, the thickness of the n-region must be increased. However, it results in slow turn-on performance.

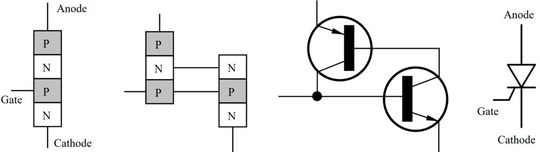

A thyristor is often represented by a connection of two bipolar junction transistors: NPN and PNP.

- PNP: Heavily doped P layer, lightly doped N layer, and moderately doped P layer form the PNP transistor (T1).

- NPN: Heavily doped N layer, moderately doped P layer, and lightly doped N layer form the NPN transistor (T2).

These two transistors are responsible for thyristor latching properties (described below).

Thyristor working principle

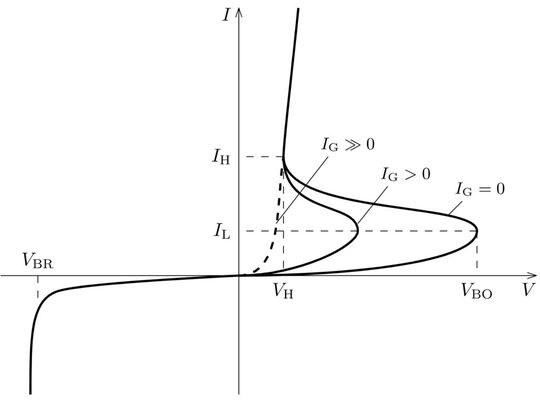

The working of a thyristor is explained through its characteristic curve. The IV characteristics of the thyristor are a graph between anode-to-cathode voltage on the X-axis and anode current on the Y-axis for different values of gate current.

It is important to note that the I-V characteristics are not considered for the second and fourth quadrants. Most thyristors are not designed for negative gate pulse operation. TRIACs are designed for the same.

The conduction of a thyristor depends on the state of three internal junctions J1, J2, and J3. They govern its ability to conduct or remain in a blocking (off) state. A thyristor will remain on when all three are forward-biased. Even if one of the junctions is reversed biased, the thyristor does not conduct and functions like an open switch.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5f/fe/5ffedb2e0ffa6/listing.jpg)

Quadrant 1: Forward-biased Thyristor

In quadrant 1, the thyristor is forward-biased. Forward blocking and forward conduction modes are explained below. Forward conduction mode is the main mode of thyristor operation in commercial use.

Forward blocking mode (IG = 0)

In this mode, the thyristor is forward-biased. A positive voltage is applied to the anode with respect to the cathode. The gate current is held to zero (open-circuited). Junctions J1 and J3 become forward-biased. But junction J2 becomes reverse biased. As one of the three junctions is reverse biased, the thyristor acts as an open switch and does not conduct.

The application of a high voltage between the anode and cathode, commonly called applied voltage, pushes the thyristor into the conducting state. A high voltage, larger than breakover voltage, facilitates avalanche breakdown in junction J2. As a result, all three junctions start to conduct. However, this process causes non-uniformity and is not safe for commercial use— it is not used in the industry.

Forward conduction mode (IG = 0)

All the connections are similar to forward blocking mode. The thyristor is forward-biased. It leaves forward blocking mode and enters forward conducting mode when the gate is triggered. Junctions J1 and J3 become forward-biased, while junction J2 reverse-biases.

Gate trigger: A current pulse is needed to trigger the gate terminal. Instead of voltage, a current pulse is necessary to inject charge carriers and change reverse biasing conditions. The applied current pulse is commonly called the gate pulse, categorized in terms of gate trigger voltage.

Depending upon the magnitude of the gate pulse, a relevant pulse width is chosen. A balance between the magnitude and width of the gate pulse avoids partial triggering. A single gate pulse is used for triggering because the thyristor latches on after triggering.

Conductive junctions: A positive pulse is applied across the gate terminal. It injects positive charge carriers into the reversed biased junction J2. The associated electric field around the depletion region in J2 results in excessive carrier multiplication— avalanche breakdown. It weakens the J2 reverse bias and promotes conductivity. All three junctions J1, J2, and J3 start to conduct electricity.

Regenerative action: As mentioned above, two internal transistors PNP and NPN form a regenerative feedback loop in a thyristor. The injection of charge carriers– initial current flow due to the gate pulse activates these two transistors.

Negative resistance: Thyristors exhibit an unstable region of negative resistance in the IV characteristic curve. As current through the thyristor increases rapidly, the voltage across the thyristor drops significantly. Thyristor voltage decreases even when all the junctions J1, J2, and J3 are conducting. The inverse relationship between current and voltage is known as negative resistance.

As per Ohm’s law, an increase in voltage increases the current flow in an electronic device, or vice versa. The concept of negative resistance states that an increase in either current or voltage decreases the other. Some authors suggest using the term “negristor” for such an occurrence. The graph below showcases negative resistance.

The left graph resembles the shape of the alphabet “N” and depicts voltage-controlled negative resistance (VCNR). The right graph resembles the alphabet “S” to show current-controlled negative resistance (CCNR). The IV characteristics of the thyristor are similar to the right graph. As the gate current pulse controls negative resistance, it makes thyristor a current-controlled negative resistance device.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c6/9e/c69eec99b61072d2ef38c8f1d160802f/0122621519v2.jpeg)

RESISTANCE

Understanding electrical resistance vs. internal resistance in power systems

Turn-on: Once the thyristor turns fully on, the voltage across the thyristor settles at a low value of about 1-2 V. The thyristor functions like a closed switch. Just like a diode, a thyristor is a unidirectional device— it conducts only in one direction.

If the gate pulse is removed, surprisingly, the thyristor does not turn off. It remains on and continues to conduct. This is because of the latching operation— regenerative action of the two internal transistors.

The collector current of the NPN transistor is the base current for the PNP transistor. Analogously, the collector current of the PNP transistor is the base current for the NPN transistor. An increase in the collector current of one transistor drives the base current of the other, reinforcing conduction.

In simple words, the transistors push the thyristor to “hold on/latch on” to the conductive state, even in the absence of a gate pulse.

Always on: Thyristors are sometimes addressed as “always on” devices— they cannot be fully controlled. But this property makes thyristors suitable for high-power industrial applications where sudden turn-off can compromise safety and business. Hence, thyristors are preferred over power transistors in high-power electronic applications.

Turn off: The thyristor can be turned off as well. In order to stay conductive, the thyristor current must remain above the holding current. Latching current is the minimum current required to keep the thyristor on after the gate pulse is removed. When the anode current is decreased below the holding current, the thyristor turns off.

The thyristor does not turn off instantly, even when the current drops below the holding current value. Residual electrons and holes remain inside the device. They may carry on the conduction process. As a result, the thyristor turns off after a short waiting period called the circuit commutated turn-off time.

Quadrant 3: Reverse-biased Thyristor

In quadrant 3, the thyristor is reverse-biased. The anode is biased negative with respect to the cathode. The gate current is kept at zero. Junction J2 becomes forward-biased. But junctions J1 and J3 become reverse biased. As junctions J1 and J3 prevent current conduction, the thyristor acts as an open switch and remains off.

As junction J2 is forward-biased, a thermally-generated small leakage current flows through the device. When the thyristor is given high voltage, junctions J1 and J3 undergo avalanche breakdown. In such cases, thyristors can face permanent damage. As a result, thyristors are not used in reverse blocking modes. Some special-application thyristors are designed to operate in reverse blocking mode.

Types of Thyristors

Any three-terminal power semiconductor device consisting of four alternating layers of PNPN belongs to the thyristor family. There are many types of thyristors used in power electronics— for a variety of applications. Some popular ones are described below.

SCR: Silicon-controlled Rectifier

The most common type of thyristor is a silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR). Both terms, thyristors, and SCRs are used interchangeably. All SCRs are thyristors but all thyristors are not SCRs. A silicon-controlled rectifier is a basic type of thyristor, which is partially controllable. SCR is used in motor control and power regulation applications.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b4/9b/b49b46625712039e0738b55aab6369a3/87458245v2.jpeg)

Semiconductors

What are diodes and rectifiers?

TRIAC: Triode for Alternating Current

A TRIAC, sometimes called a bilateral triode thyristor, belongs to the thyristor family. Unlike classic thyristors, they can conduct electricity in both directions. A negative or positive gate pulse is used to trigger a TRIAC. Once it starts conducting, it moves onto a latching state. Just as the name suggests, the Triode for alternating current is used in AC applications.

DIAC: Diode for Alternating Current

DIAC— Diode for Alternating Current is a combination of a diode and a thyristor. DIAC is called a diode because it looks like a diode and has two terminals. However, unlike diodes, it is a bidirectional device. DIAC is a part of the thyristor family due to its alternating five-layer NPNPN structure. This device is a diode used for AC applications.

GTO: Gate Turn-off Thyristor

A GTO is among the most common thyristor types used in high-power applications. GTO are of two types: asymmetrical and symmetrical. Asymmetrical GTOs are commonly used in variable-speed motor drives and high-power inverters.

Unlike classic thyristor, GTO uses a negative gate pulse for instant turn-off. GTO is a fully controllable device. However, GTOs suffer from long-switch off time.

MCT: MOS-controlled Thyristor

A MOS-controlled thyristor is a voltage-controlled device consisting of two MOSFETs built into the gate structure. One MOSFET, also known as ON-FET, turns on the device. Another MOSFET, or an OFF-FET, is responsible for the MCT turn-off process. Internally, two BJTs perform the thyristor latching action.

IGCT: Integrated Gate Commutated Thyristors

Structurally similar to GTO, IGCT is a fully controllable thyristor. Not to be confused with IGBT– A transistor type. The word “gate commutated” shows that the gate terminal turns off the device by commutating the current. It exhibits low power losses and a switching frequency of up to 500 Hz. IGCT is used for switching large amounts of current in industrial power electronic applications.

SITh: Static Induction Thyristor

The static induction thyristor was invented two decades after the SCR. SITh is an improved version of thyristor that consists of a heavily doped p-type buried gate structure. Compared to other thyristor technologies, SITh exhibits faster switching periods of about 0.25 microseconds. It turns off quickly, handles large currents, and has high forward voltage blocking capability.

Optically Triggered Thyristors

Optically gated thyristors or light-triggered thyristors (LTTs) use incident light rays, instead of current pulses, to trigger the gate terminal. These devices fall under the category of optoelectronics and are used in power utility and VAR compensation systems. Optically gated thyristors are used to handle large voltages up to 6 kV, currents up to 2 kA, and power up to 10 mW.

Thyristor weight and packages

Based on lateral dimensions, thyristors are one of the largest semiconductor devices that exist. A 10 cm wide silicon wafer is capable of manufacturing a single thyristor. They weigh from 10 grams to several kilograms, depending upon the power ratings and applications. Unlike transistors, thousands or millions of thyristors cannot be integrated into chips. They come in various packages:

- Small plastic packages for low-power thyristors.

- Stud-mount packages for medium-power thyristors.

- Press-pack packages for high-power thyristors.

Thyristor applications

Thyristors are applicable in a variety of industries— they are mostly found in factories.

Thyristors still exhibit one of the largest power-handling capabilities in the world of power electronics. The main applications of thyristors are described below.

Power electronics

Thyristors are capable of withstanding large voltages and delivering large currents in power electronics applications. They are used to function as ideal open or closed switches for controlling power flow in a circuit.

Power conditioning

Thyristors are used in power conditioning systems that need to control voltages higher than 1 kV and currents higher than 100 A.

HVDC transmission

Thyristors are used in HVDC transmission as line frequency phase-controlled rectifiers. HVDC systems use thyristor valves to convert DC to AC and AC to DC, arranged in multi-stack layers.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/60/a6/60a6321aee790/seddik-bacha.jpeg)

KEYNOTE PCIM EUROPE 2021

HVDC grid challenges locks and opportunities

Motor control

Thyristors are used in the first stage of electric motor drive to control the voltages across the windings. They are typically used in variable-speed drives, traction motors, and soft starters.

Power conversion

Thyristors are used in controlled rectifiers— AC to DC in high-power applications and inverters— DC to AC in uninterrupted power supplies. They are typically used in current source inverter (CSI) topologies.

AC circuits

Thyristors are commercially used in some AC power circuits to control and optimize the flow. They can convert AC power at one amplitude and frequency to AC power at different values. Applications include light dimmers, fan speed controllers, and heater control.

Utility inverters

Thyristors can be used in three-phase DC-AC utility inverters.

Reactive power control

Thyristors are used with inductors and capacitors to control reactive power in a system.

Protective circuits

Thyristors are used in protective circuits like snubber circuits, circuit breakers, surge protection devices, crowbar circuits, and power factor correction systems.

Renewable energy systems

Thyristors are used in vehicle ignition switches, wind and solar power inverters, and battery chargers.

Digital electronics

Due to their bistable switching functionality, thyristors are used in digital electronic applications such as logic circuits, phase control, oscillators, and level detectors.

Thyristor advantages

Thyristors provide several benefits that enhance their suitability for power control applications, including the following:

- Thyristors exhibit the largest current conduction capabilities among all semiconductor switches.

- Thyristors can block the highest amount of voltages for any other solid-state switching device.

- Thyristors are highly reliable in controlling large amounts of power.

- Thyristors have simple gate driver circuits.

- Thyristors are easier to operate.

- Owing to packaging, Thyristors can exhibit good thermal and electrical performance.

- Thyristors have a long life.

- Thyristors are cost-friendly.

- Cathode shorts can easily limit dv/dt displacement current effects.

Thyristor disadvantages

Despite their advantages, thyristors also have several drawbacks that can impact their performance in specific applications, such as:

- The diffusion processes of forward and reverse blocking modes are quite long.

- Thyristors are not fully controllable devices.

- Thyristors are slow. They are unreliable for high-frequency applications.

- Thyristors are minority-carrier devices.

- High temperatures can affect the performance of thyristors.

- Thermally-induced leakage current can self-trigger the thyristor.

- In high voltage and current applications, thyristors can dissipate excessive heat during turn-off.

- Thyristor turn-off is a complicated slow process. The external circuit must reverse bias the thyristor to initiate the turn-off procedure.

- Thyristors exhibit large reverse recovery currents.

- Thyristors are susceptible to voltage spikes and noise.

Why use Thyristors instead of power transistors?

A variety of power electronic devices are available in the market. The most common ones are power transistors. The section explains why you should bet on thyristors instead of transistors.

High-power handling

We use thyristors instead of power transistors due to their ability to deal with high power. A power transistor is hardly capable of handling a kilo volt and a few amperes of current.

On the other hand, a thyristor can handle voltages and currents in the order of several ten thousand. In industrial and HVDC applications, a thyristor can deal with millions of watts, something that power transistors cannot do.

Latching

What makes thyristors different from other power electronic devices is their latching property, which is a major reason for choosing thyristors over power transistors. As mentioned above, the thyristor is an always-on device. It remains on even after the gate pulse is cut off.

A power transistor would completely fail when the supply voltage is cut off. With the help of thyristors, industrial and HVDC applications can constantly “enjoy” power and carry out their tasks. However, IGBT is the only transistor technology that can surpass thyristors in terms of power handling capabilities.

| Feature | Transistor | Thyristor |

| Structure | Three-layer | Four-layer |

| Number of terminals | Three-terminal | Three-terminal |

| Terminal | BJT: Base, collector, and emitter MOSFET: Source, drain, and gate | Anode, cathode, and gate |

| Control mechanism | Voltage-controlled or current-controlled | Current-controlled |

| Controllability | Fully-controllable | Partially controllable |

| Component type | Active | Active |

| Negative resistance region | Absent | Present |

| Latching behavior | Absent | Present |

| Turn-off | Easy | Complicated |

| Function | Amplification and switching | Bistable switching |

| Switching speed | Fast (nanoseconds to microseconds) | Very slow (Microseconds to milliseconds) |

| Types | BJT, FET, IGBT, and many more | SCR, GTO, MCT, and many more |

| Voltage and current handling capabilities | Low Less than 100 V and a small current of about 10 A | High-power — Higher than 1 kV and 100 A Medium power: Lower than 1 kV and 100 A |

| Power handling capability | Low to moderate power from W to a few kW | Moderate to high power between kW to MW |

| Scalability | Very high (Billions and trillions in chips) | Limited— found only as discrete components, modules, and chips (rare) |

| Applications | Switching, amplification, on-chip operation, signal processing, and many more | Industrial power electronics like motor control, HVDC, and many more |

References

- Mohan, N., Undeland, T. M., & Robbins, W. P. (n.d.). Power Electronics: Converters, Applications, and Design (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Rashid, M. H. (Ed.). (2001). Power Electronics Handbook. Academic Press.

(ID:50376642)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/63/c7/63c7da97be945/diotec.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/66/8b/668becd1c07eb/dowa-logo-word--1-.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/21/7f/217fcc66cf062b3e3212dcb6c2d53992/0124480366v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3d/21/3d2163e1c620c06fa94740403dd297d1/0123860891v2.jpeg)