THERMAL SOLUTION Mastering thermal design: heat pipes calculators for engineers

Related Vendors

Managing heat is one of the biggest challenges in high-power, compact electronic systems, from inverters and DC/DC converters to automotive power modules. Heat pipes offer an efficient solution by transferring thermal energy through phase-change cycles, achieving far higher conductivity than traditional solid materials. Online heat pipe calculators allow engineers to quickly estimate performance and feasibility, streamlining the design of reliable and compact thermal management solutions.

When combining high power density with a compact design, heat becomes the limiting factor. This can manifest itself in an inverter, a DC/DC converter, or an automotive power module, where components lose efficiency or fail without proper thermal management.

Heat pipes as a leading thermal solution

Heat pipes are a very effective solution for thermal management due to their high thermal conductivity and ability to efficiently transfer heat through an evaporation and condensation cycle.

The phase change principle of the working fluid for heat transfer is a process that heat pipes leverage to achieve significantly greater efficiency than traditional solid conduction using materials like copper or aluminum.

Online heat pipe calculators are used to help engineers estimate the thermal performance and feasibility of a heat pipe in a specific design application. Without the need for complex simulation software or initial physical testing, designers can perform quick, preliminary calculations.

The pillars that support its high efficiency

The key factors that make a heat pipe so efficient are:

- Use of Latent Heat of Vaporization: When the working fluid evaporates at the hot end, it absorbs a large amount of heat. Then, the vapor travels to the cold end and condenses back into a liquid, releasing that same large amount of heat. The speed and efficiency are remarkable in this latent heat transfer.

- Superior Effective Thermal Conductivity: Compared to that of solid copper, the effective thermal conductivity of a heat pipe can be up to 1,000 times greater thanks to the phase-change cycle.

- Low Internal Thermal Resistance: Due to the minimal thermal resistance in the gaseous phase, heat transfer by steam is very rapid, traveling through the open space of the tube with negligible temperature loss.

- Passive and Continuous Operation: The process consists of a closed, self-sustaining cycle in which the condensed liquid returns to the hot end without the need for mechanical pumps (or by gravity if the orientation is favorable). The absence of moving parts ensures consistent and highly reliable system performance.

- Near-Isothermal Operation: Components are kept within safe temperature ranges because the heat pipe can move heat with a very small temperature drop between the hot and cold ends.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/9a/af/9aafa5ad3d3d900a6e22adf6d06a9bf5/0126877798v2.jpeg)

OPTIMIZATION TECHNIQUES

Heat management methods in power modules

Design and operation of a heat pipe

The principle of evaporation and condensation is at the heart of how a heat pipe works and the fundamental reason for its high efficiency. The process is a continuous, passive cycle that transfers large amounts of heat from one end to the other, utilizing the latent heat of the working fluid.

The cycle unfolds in three main sections within the vacuum-sealed tube:

In the evaporator section (hot end), when heat is applied to one end of the tube (for example, from a hot electronic component), the working fluid in the wick structure or at the bottom of the tube absorbs that thermal energy.

In this way, the liquid reaches its boiling point and turns into vapor. This process consumes a large amount of latent heat of vaporization, effectively cooling the hot surface.

In the transport section (adiabatic zone), the generated steam creates a pressure difference within the tube, allowing it to travel rapidly to the cooler end. Ideally, this central section is insulated, minimizing heat loss during steam transport.

In the condenser section (cold end), the vapor comes into contact with the tube walls, which are connected to a heat sink or an external cooling system. This cools the vapor and releases the latent heat it had previously absorbed.

Through condensation, the vapor returns to its liquid state and collects in the wick structure on the inner walls of the tube.

To ensure the condensed liquid returns to the hot end, capillary action is used via the porous structure of the wick (which acts as a passive pump with no moving parts). If the condenser is above the evaporator, gravity can also assist in the fluid return.

The capillary structure (or wick) of a heat pipe is an internal porous structure that returns condensate to the evaporator through capillary action (which acts as a passive pump with no moving parts). The working fluid is a special liquid (such as water, ammonia, or methanol) that evaporates in the hot zone and condenses in the cold zone, efficiently transferring heat.

Among the materials used in heat pipes are copper and aluminum for their high conductivity, or stainless steel and titanium for corrosion and high-temperature resistance.

The variety of designs shows that smooth tubes are the most economical and easiest to clean, with low pressure drop. On the other hand, finned tubes increase surface area for more efficient heat transfer, and tubes with internal grooves create greater turbulence in the fluid, which improves heat transfer and allows for more compact designs.

The most significant advantage of heat pipes over conventional heat sinks made of materials like aluminum or copper lies in their superior heat transfer efficiency.

Having an effective thermal conductivity hundreds or thousands of times greater, they transfer heat by moving far more energy per unit mass and time than conduction through a solid metal.

Heat pipes are notable for quickly absorbing and dispersing heat from highly concentrated hot spots (such as a CPU or GPU chip) and distributing it evenly over a larger fin surface.

For a given cooling capacity, a heat pipe-based solution can be lighter and more compact than an equivalent solid heat sink, which would have to be much larger or made of a denser material (such as copper) to achieve similar performance.

In a heat pipe, the temperature drop during transfer is very small (almost isothermal) from one end to the other, unlike a solid metal block where the temperature decreases noticeably as one moves away from the heat source.

Heat pipes are used in power modules as a highly efficient thermal management solution to dissipate the heat generated by electronic components such as transistors, diodes, and transformers. They allow heat to be moved from confined spaces to areas away from other heat-sensitive components.

In the battery of electric vehicles (EVs), heat pipes transfer heat from cells to keep them within their optimal temperature range, thereby preventing premature degradation, optimizing performance, and avoiding safety risks.

High-pressure vacuum tube (HPVT) heat pipes are widely used in solar collectors to heat water or a working fluid for heating. In photovoltaic solar system inverters or frequency converters in wind turbines, heat pipes are used to efficiently extract heat from hot spots in power electronic components (IGBTs, MOSFETs).

In sealed industrial cabinets that protect electronic components (PLCs, inverters, power supplies) from dust and moisture, heat pipes are integrated into air-to-air or air-to-water heat exchange systems to efficiently draw internal heat to an external heat sink without compromising the cabinet's seal.

Calculation Tools for Heat Pipes Design

These simplified simulation tools serve as a crucial first step in the process of designing efficient thermal management solutions. The main purposes and benefits of these tools include:

- Determining the Maximum Heat Transfer Capacity (Qmax): Knowing the physical dimensions and operating conditions of a heat pipe, you can calculate how much thermal power it can efficiently transfer. This is crucial to ensure the heat pipe can handle the thermal load required by the device being cooled.

- Evaluate Design Feasibility: The goal of these tools is to determine if a heat pipe of a standard size and material will work in the desired application (e.g., cooling a CPU or an industrial component).

- Compare Different Configurations: To help users understand how the overall performance of the designed tube is affected, different parameters can be quickly tested, such as tube diameter, evaporator length, condenser length, and orientation (horizontal, vertical, etc.).

- Estimating Thermal Resistance: To perform the thermal analysis of the entire system and predict the operating temperatures of the components, these tools provide an estimate of the total thermal resistance of the heat pipe.

- Material and Working Fluid Selection To help you choose the most suitable combination for the application's temperature range, more advanced calculators allow you to select different working fluids (such as water, methanol, ammonia) and casing/wick materials.

- Facilitating Preliminary Decision Making: To determine whether heat pipes are the optimal solution or if a different or customized cooling approach is required, these tools provide essential engineering data to accelerate the initial design phase.

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/66/4e/664efb5ea2f9e/wp-dc-dc-book-of-knowledge-recom-coverbild.png)

Online Heat Pipes Calculators Comparison

To obtain approximations of the performance of heat pipes, web-based estimation tools such as online heat pipe calculators from manufacturers like Advanced Cooling Technologies (ACT), Celsia, and Boyd (Aavid) are used.

| Feature | ACT (Advanced Cooling Technologies) | Celsia | Boyd (Aavid) |

| Tool Type | Online web-form calculator | Online web-form calculator | Online web-form calculator |

| Primary Output | Heat transport capability curves (Qmax vs. Delta T) | Max Heat Carrying Capacity (Qmax), Thermal Conductivity, Thermal Resistance, Delta-T | Max Heat Transfer (Qmax) at various temperatures/powers |

| Inputs | Length, Evaporator/Condenser sizes, Height, Power, Temperature | Length, Diameter, Orientation, Condenser/Evaporator lengths, Heat load, Wick material selection | Overall length, Evaporator/Condenser lengths, Power/Temp, Orientation, Diameter |

| Working Fluid | Water | Water | Water |

| Wick Material | Standard wick | Standard/Performance sintered wick | Standard sintered wick |

| Material | Copper | Copper | Copper |

| Specificity | Focuses on performance curves and engineering contact | Provides detailed thermal properties | Estimates performance for specific off-the-shelf heat pipe geometries |

| Limitations | First-order approximation; requires engineering consult for complex applications | First-order approximation; based on empirical data & theoretical equations | First-order approximation; requires specific geometric inputs |

All three tools are designed around the most common standard configuration of heat pipes: a copper wrapper with water as the working fluid and a sintered powder metal wick.

Without claiming to deliver detailed engineering simulations, these calculators offer initial feasibility checks and performance estimates. While useful for the early stages of design, they require consultation with engineering teams for complex applications.

While the main function of the calculators is similar across the different models, there are differences in the user interface for presenting inputs and outputs. While ACT emphasizes curves, Celsia focuses on specific thermal values.

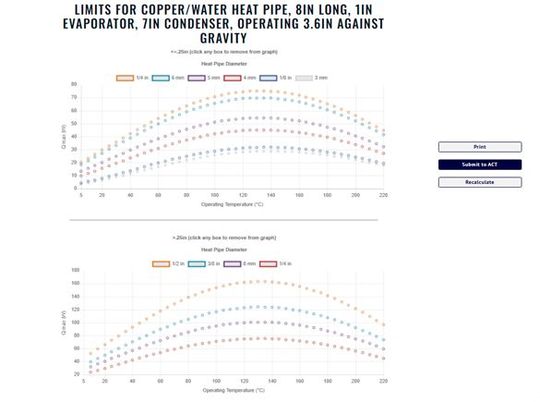

Advanced Cooling Technologies (ACT) Calculator

Advanced Cooling Technologies (ACT) provides a free online Heat Pipe Calculator tool designed to help engineers quickly estimate the thermal performance and feasibility of standard copper-water heat pipes for specific applications.

To use the calculator, users must provide the following application-specific parameters:

- Heat Pipe Length: The total length of the heat pipe.

- Evaporator Length: The length of the section in contact with the heat source.

- Condenser Length: The length of the section in contact with the heat sink.

- Diameter: The diameter of the heat pipe.

- Orientation (Height Against Gravity): The vertical orientation or height difference between the evaporator and condenser sections. A negative value is used if the evaporator is below the condenser, assisting liquid return via gravity.

- Operating Temperature: The desired operating temperature of the heat pipe.

To determine the performance of a heat pipe, the calculator uses this input data to evaluate several key heat transfer constraints. Based on the given parameters, determine which of these physical limits will be reached first:

- Capillary Limit: The maximum heat transfer rate the wick can sustain before it can no longer return liquid to the evaporator fast enough via capillary action. This is heavily influenced by orientation and working fluid properties.

- Boiling Limit: The maximum heat flux the evaporator surface can handle before the boiling becomes unstable and creates dry spots.

- Entrainment Limit: The maximum velocity the vapor can achieve before it starts to pull liquid droplets away from the wick structure back towards the condenser end.

After performing these calculations using its internal models, the calculator provides a results graph and/or numerical output.

- 𝑄𝑚𝑎𝑥 (Maximum Heat Load: The primary output is the maximum amount of heat (power in Watts) that the heat pipe can transport under the specified conditions without failing (hitting one of the limits).

- Effective thermal conductivity: Based on the calculated 𝑄𝑚𝑎𝑥, the effective thermal conductivity (W/m·K) is presented.

- Graphical Representation: To help the user visualize the performance range, the tool displays a curve indicating the maximum capacity within a temperature range.

By applying validated thermal management formulas and data for copper-water heat pipes, the ACT calculator functions as a rapid engineering tool. Based on a given configuration, quickly identify the most significant physical limitation and estimate the maximum heat load the pipe can reliably withstand.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/46/65/46650c82406138e0a156d8b63d03f4a2/0128386832v2.jpeg)

THERMAL EFFICIENCY

New cooling packaging technology to drive efficiency in applications

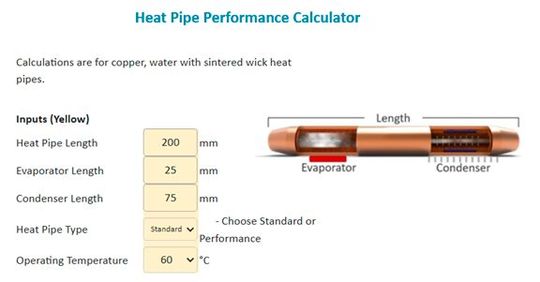

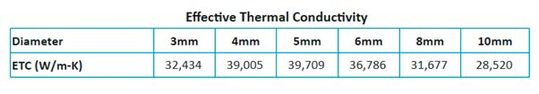

Celsia Design Tool Calculator

Celsia offers a free, web-based Heat Pipe Calculator tool on its website to help engineers estimate the performance of copper/water heat pipes using a sintered wick structure. It is designed for quick, initial estimates and provides performance curves and tables based on the input values.

To use the calculator effectively, users need to provide several input parameters:

- Heat Pipe Length (total length).

- Evaporator Length (length of the heat source contact area).

- Condenser Length (length of the heat sink contact area).

- Condenser Length

- Operating Temperature(average of max case and max ambient temperatures).

- Heat Pipe Type (Standard or Performance sintered wick material).

- Orientation (maximum height the heat pipe operates against gravity, or negative if gravity-aided).

The tool provides essential data for the design and analysis of thermal management systems:

- Heat Pipe Carrying Capacity (Qmax): The maximum power (in watts) the heat pipe can transport, factoring in its angle of orientation (e.g., horizontal vs. against gravity).

- Effective Thermal Conductivity (Keff): A calculated value used as an input for CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) modeling.

- Thermal Resistance (Rth): The temperature difference (delta-T) from one end to the other for a given power input.

- Qmax vs. Angle of Operation: A chart and table show the maximum power capacity at various angles of orientation. Use a safety factor (typically derated by 20-25%) for reliable design.

- Power vs. Delta-T: A chart and table show the temperature difference across the heat pipe for a given power input. You can calculate the thermal resistance (Rth) by dividing the delta-T by the input power (Rth = Delta-T / Power Input).

Considerations to keep in mind

Online heat pipe calculators provide quick results for initial design assessments, saving significant time and effort compared to manual calculations or detailed simulations.

Most of them feature an intuitive, step-by-step interface that requires only basic input parameters (e.g., heat pipe length, diameter, orientation, power) and are readily available online for free requiring no specialized software or expensive equipment.

These tools work by automating calculations based on established formulas, helping to reduce the possibility of manual mathematical errors.

A key limitation is that these calculators often rely on standard conditions (e.g., specific materials like copper/water heat pipes and sintered wicks), which can reduce their accuracy when modeling different designs or materials.

Furthermore, they lack the detailed visual description or in-depth analysis offered by more sophisticated graphics-based simulation software, and data from existing technical drawings often needs to be transferred manually.

The concepts presented in this article demonstrate that the future of thermal design is not based on a single tool, but rather on the integration of emerging technologies that address the increasing demands for efficiency and complexity in heat management. This convergence of simulation, AI, and the cloud represents a paradigm shift in how engineers approach thermal challenges.

Those who understand their thermal journey from the outset avoid overheating and accelerate time-to-market.

(ID:50666659)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/62/b9/62b980cddf5d6/ceramtec.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/66/8b/668becd1c07eb/dowa-logo-word--1-.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/f0/d7/f0d77d36f1cd3852fc0ce0d3343d8aec/0128634905v1.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4c/38/4c38b08984d55056a4814adb953d3188/0128634908v1.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/96/de/96dea6ac9dc992b4a5a38593c94b9466/0128634914v1.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b8/c2/b8c223714a162f01a7a3b6a453efbf2a/0128634932v1.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/25/a5/25a5f03b687b18a3dbff3e43b16c9075/0126765129v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/9a/af/9aafa5ad3d3d900a6e22adf6d06a9bf5/0126877798v2.jpeg)