RIPPLE CURRENT Do you know the ripple current in your capacitor?

Related Vendors

High-voltage electrolytic capacitors are familiar components in the power conversion landscape. Often used for filtering applications, they undergo a permanent stress due to the circulation of rms current. It is therefore important to determine this heating contributor and choose a capacitor type offering adequate design margins. This article gives some hints on how to select the right capacitor.

Capacitors are used in a wide variety of applications ranging from small-signal active filters to high-current power electronics converters. In this latter, the capacitor is selected based on different criteria such as acceptable output voltage ripple, operating voltage, size and cost. However, the utmost important parameter remains the ripple current expressed in root mean square (rms) amperes. When circulating, this current will internally heat up the capacitor and increase its internal pressure, potentially provoking a catastrophic failure over time. These are the classic pictures you can see on the Internet when searching for “bad caps” or read the Wikipedia article on the subject of capacitor plague.

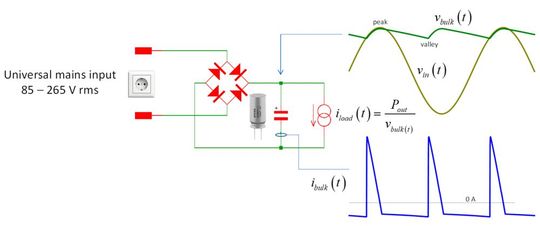

In this article, we will look at the most common usage of an electrolytic capacitor which is the rectification of an alternating voltage. The ac voltage can come from a stepdown transformer or directly from the mains in an ac-dc switching converter as illustrated in Figure 1.

The waveform in the right-side of the picture – vbulk(t) – describes the voltage ripple captured across the capacitor. If the input frequency is 50 Hz or 60 Hz as in the US, then the capacitor ripple frequency will be at twice that value. With a weak rejection capability from the downstream converter – we talk about audio-susceptibility – or in heavy-load conditions, you can sometimes observe this 100- or 120-Hz component in the regulated output voltage. It is an indication that the loop struggles to deliver the rated power at the lowest line input, and you may need to take action.

In this picture, you see the load modeled by a current source which draws a current iload. This current is actually permanently adjusted by the regulating converter to keep a constant output power. If we assume a 100 % efficiency, then Pin ~ Pout and iload(t) ~ pout(t)/vbulk(t): considering the constant power delivered by the converter, the absorbed current is minimum at the bulk peak but increases significantly in the valley. For optimal operation, the converter must be designed to deliver its nominal power at this low value otherwise regulation may suffer as previously underlined. This worst-case scenario occurs at low line and must be carefully studied to avoid premature over-load protection with too deep a valley. This voltage will go lower as the capacitor ages and design margins must exist, as always.

The current in the capacitor is made of two components: a refueling 100- or 120-Hz peak current and high-frequency pulses permanently absorbed by the converter. The refueling event is very narrow and, during this time, the capacitor stores energy while some of the current feeds the converter. When the input sinewave passes its peak, the capacitor takes over and supplies the load by giving back the stored energy: its voltage drops to the valley until another peak comes up. During the entire cycle, the converter switches at high frequency and absorbs current pulses whose signature depends on the adopted topology and its operating mode. This high-frequency current also participates to the capacitor heat-up and must be accounted for.

The current seen by the mains looks like triangular sections as in the simulation when the output impedance of the grid is almost zero. When a front-end EMI filter is installed, it naturally reduces the peak and the current is rounded, slightly reducing the harmonic content and the rms value in the end.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/f4/ae/f4ae74243cba68677697623180e5fb70/0117195607.jpeg)

BASIC KNOWLEDGE

An introduction to power converters

What capacitor value?

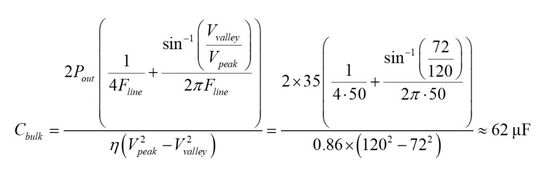

The required capacitance can be obtained by using a formula I derived in this document available online:

For instance, for a converter delivering 35 W from a 50-Hz 85-V rms input (~120 V peak) with a 86 % efficiency, you will need a 62-µF capacitor. With this value, the valley voltage will be 72 V, corresponding to a 40 % ripple voltage, a classic selection in these applications. In reality, knowing the tolerance associated with this component, it is likely that you consider a part featuring the normalized value of 82 or 100 µF in the end.

Identifying capacitor constraints

A capacitor can be selected based on different electrical or physical parameters but those of utmost importance are voltage and operating temperature, closely linked with the rms current for the latter. As the temperature rises and approaches the maximum specified in the datasheet, a derating factor must be respected to obtain the longest operating lifetime. In voltage, it is not uncommon to see derating factors approaching 30 % of the maximum voltage for aluminum electrolytic types with a recommendation to increase this safety margin further as the part heats up. In our travel adapters, when operated at the lowest input (85 V rms), the rectified voltage peaks at 120 V and can increase up to 180 V in the North American market (127 V rms). If you now plug the same adapter in a European outlet, the mains can be as high as 265 V rms (the maximum of the nominal 230-V rms specification) and biases the bulk capacitor at a 375 V level. Based on these figures, designers chose their bulk capacitor according to the highest input voltage and 400-V types are very popular. Considering a nominal high-line operating voltage of 325 V (230 V rms nominal), it brings a derating factor of ~19 % for the capacitor in normal operating conditions.

Capacitor temperature is affected by the rms current flowing in the component and the ambient temperature in which it operates. The rms current must be assessed in the worst-case condition and should guide your capacitor selection. Ignoring this important stage can severely shorten the operating lifetime with possible failure in the end. You can either analytically compute the current as in [1] or rely on simulation to assess the rms content of the current circulating in the capacitor.

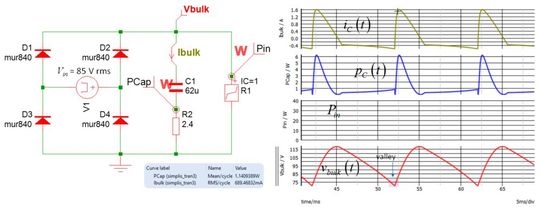

Figure 2 shows a typical example with a SIMPLIS® circuit delivering the results in a few seconds. Please note the presence of the 2.4-Ω equivalent series resistance (ESR) computed for a typical dissipation factor (tan ) of 0.2 with a 20-°C temperature and a 120-Hz ripple current. The load is a 35-W adapter in this example. In the simulation the valley voltage is below 75 V and you will use this value for sizing the 35-W converter with margin. Past the in-rush surge, the rms current for the capacitor stabilizes around 690 mA. In this simple setup, the current is made of 100- or 120-Hz cycles but does not include the high-frequency pulses representative of the downstream converter signature. These pulses will also heat up the capacitor and must be accounted for in the evaluation process.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/98/83/9883bec0993dcc43a974f24ac960d6f6/88514339.jpeg)

ENERGY STORAGE

Supercapacitor: Workings and applications

Selecting the right capacitor

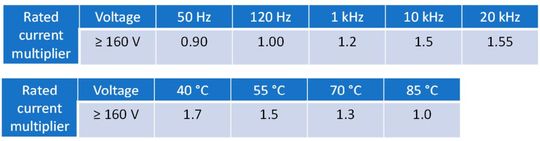

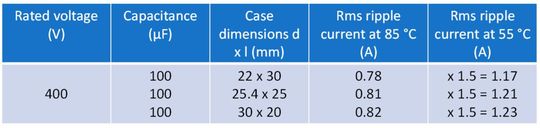

Depending on the operating temperature, the maximum allowable rms current significantly changes. As with many power components, using the capacitor below its maximum temperature lets you pass more current. The below typical table shows that for a capacitor rated at an 85-°C temperature, the authorized maximum rms current stated at this extreme temperature value is increased by 50 % if you consider an operating temperature of 55 °C.

A similar remark applies to the ripple frequency where the worst case corresponds to the lowest frequency: the high-frequency pulses absorbed by your converter should have a lesser impact than the 100- or 120-Hz ripple and it is fortunate. Considering our 35-W adapter and if we limit the maximum temperature of the capacitor to 55 °C, then a 100-µF type accepting a current of ~730 mA at 85 °C will do the job in this particular example.

As confirmed by table 2, any of the three highlighted components are potential candidates, providing adequate design margin.

A design example

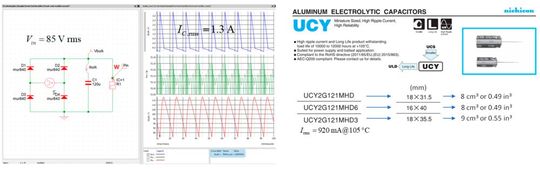

Assume this time we want to determine the front-end capacitance for a 65-W power supply operated on universal-mains, down to 85 V rms. Considering a 42 % ripple and an acceptable valley voltage down to 70 V, the capacitance is calculated to 112 µF, normalized to the upper value of 120 µF. The simulation from Figure 3 reveals a ripple current of 1.3 A rms and a valley voltage of 75 V or so. After browsing Nichicon’s offer for 400-V aluminum types, there could be three potential candidates from the UCY series when operated below the maximum temperature of 105 °C.

The volume of these capacitors lies around 8-9 cubic centimeters (0.49-0.55 cubic inches) and could support the entire input voltage span alone. Beside Nichicon, Surge Components offers a rich selection of capacitors for these rectifying functions and parts in the RXB (5000 hours) or RLD (12000 hours) series should also fit the bill. Finally, NIC Components with its NRE-H or -HS can also represent a viable choice.

Conclusion

The operating current of a capacitor is an extremely important operating parameter which can affect product reliability if overlooked during the design stage. Determining this current can be easily done with a simulator and will let you find the type among the brands we distribute which provides adequate design margin.

Reference

1. C. Basso, Switch-Mode Power Supplies: SPICE Simulations and Practical Design, second edition, McGraw-Hill 2014

Power Electronics in the Energy Transition

The parameters for energy transition and climate protection solutions span education, research, industry, and society. In the new episode of "Sound On. Power On.", Frank Osterwald of the Society for Energy and Climate Protection Schleswig‐Holstein talks about the holistic guidance his organization can provide.

Listen now!

(ID:50196440)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/2f/f3/2ff3221bf7665de2d0acf83760bfd1fa/0130031523v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/c3/16/c316e955a97f5d72d9678297b237b9e5/0129932858v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ef/0a/ef0adb0acf793fe147cc27c21f6a7a67/0129954238v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/53/f9/53f9301dfc9292d02960f7996c79cc6e/0129927601v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/cd/6ecd41d095d5111cf4ed37b714844487/0129930878v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/02/c0/02c0e9722f70b1134dbf96fb59a9c73d/0129655179v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cc/67/cc670ea2029cd2af5c641af70e1bf734/0129816392v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/e6/eae6aee30071e67a5627027974437134/0129544613v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/5e/b15ee02b0ba02db70cf61e37d66ad1d3/0129349127v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/26/d5/26d591cc340077026eac56a0e7564faf/0129949603v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/4d/e0/4de02f76a37cbb3df30dd231de589c8e/0128866890v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/18/0b/180b7b63afc91e523592d8a5ce161c96/0129847487v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/be/c8/bec8d43fc0ee73414274be44608b2970/0129748903v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/thumbor.vogel.de/mguFAwuAxCGw9kVi3c_k2-HNi5I=/500x500/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/66/74/667444027a724/tof1.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/63/c7/63c7da97be945/diotec.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/62/a0/62a0a0de7d56a/aic-europe-logo.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/68/2c/682c3e2e9a195/logotype-rvb.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/52/ba/52bad13a953b2f02f0344af930d198a1/0123734944v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/8c/1a/8c1a6f87a2af9653a5df2d5d963915c0/0118206891v2.jpeg)