COMPONENT AGEING Degradation and aging of power-electronic components

Related Vendors

Every component in power electronics experiences degradation over time, from semiconductors and capacitors to inductors and connectors. Thermal stress, material fatigue, and irreversible entropy processes determine how quickly parts age. Normalized KPIs and visualizations, such as radar plots, help engineers detect wear, plan maintenance, and make realistic lifetime predictions.

All components in power electronics degrade over time. This is not a matter of “if,” but of “how fast.” At the most fundamental level, the second law of thermodynamics ensures that materials evolve from order to disorder, generating entropy [Bauer, 2015]. In practice, this manifests as diffusion, dislocation accumulation, polymer chain scission, oxidation, and crack growth.

Why Arrhenius?:

Many degradation processes are governed by thermally activated atomic or molecular events. Diffusion, chemical reactions, and bond breakage require activation energies on the order of electronvolts. The probability of such an event rises exponentially with temperature, giving rise to the Arrhenius relation. Consequently, a rise of just 10 °C typically halves lifetime for mechanisms with E_a ≈ 0.6–0.9 eV [Venkat, 2002; IEC, 2013]. This universality explains why temperature control is the single most powerful lever in slowing degradation.

1. Semiconductors

Semiconductors are at the heart of every power-electronic system. They fall into three groups: system-function relevant devices (processors, FPGAs, IGBTs, MOSFETs), which directly determine performance and capability; auxiliary devices (controllers, references, memories), which support main functionality but are less stressed; and non-differentiating devices (glue logic, level shifters), which are necessary but easily replaceable. Their degradation mechanisms differ mainly in severity and system impact.

1.1 System-function relevant devices

These devices carry either the main switching load (MOSFETs, IGBTs, SiC/GaN) or central logic functions (processors, FPGAs). They face NBTI/PBTI, TDDB, EM, and package-related fatigue. For example, MOSFET R_\text{DS(on)} typically increases 5–20 % as bond wires degrade [Ciappa, 2002], while IGBT die-attach fatigue can raise thermal impedance by 10–50% [Zhang, 2014].

- Supplier strategies: use thicker oxides, copper clip interconnects, or sintered die attach. These measures increase robustness but also cost (larger die, slower processes, expensive bonding).

- Design strategies: derate current density, use redundant parallel devices, match thermal expansion of substrates. These rely on knowing the real stress environment.

Failure modes: timing errors, EM opens, bond-wire lift-off, runaway from poor thermal conduction.

1.2 Auxiliary devices

Auxiliary semiconductors — DCDC controllers, LDOs, ADCs/DACs, small MCUs, memories — degrade more slowly but still drift. Bandgap references typically shift ±0.5–2 % over 10 years at 85 °C [Saha, 2006]. Memory bit retention errors rise with stress [Ielmini, 2011].

- Supplier strategies: select analogue-optimised nodes with thicker oxides, integrate ECC in memory. Adds cost in die area or lower density.

- Design strategies: employ calibration, redundancy, or watchdog timers, tailored to application requirements

Failure modes: reference drift, bit errors, loss of timing margin.

1.3 Non-differentiating logic

Glue logic and level shifters rely on mature CMOS. Thresholds may drift 10–30 mV over a decade [Kaczer, 2005], but design margins usually mask this.

- Supplier strategies: higher-voltage tolerant processes increase robustness at the cost of larger devices.

- Design strategies: allow slack in timing and voltage budgets

Failure modes: rare logic-level errors if margins are exceeded.

2. Inductors

Inductors store energy magnetically. Their performance depends on the magnetic core and the insulation of their windings. Over time, ferrites exhibit permeability drift of ±3–10 % and rising loss tangent [Shokrollahi, 2017], while enamel insulation embrittles, with dielectric strength falling 20–50 % over 20 000 hours [IEC, 2013].

- Supplier strategies: stabilise ferrite grain boundaries by doping; use higher-class magnet-wire enamels. These choices add material cost.

- Design strategies: oversize inductors to reduce hot-spot temperature, or impregnate to block moisture — decisions tied to system stress.

Failure modes: inductance loss (affecting EMI filters), higher core loss leading to heating, winding shorts.

3. Capacitors

Capacitors are the most common wear-out element. Electrolytics suffer electrolyte dry-out: capacitance falls 20–40 %, ESR rises 2–6× [Venkat, 2002]. Film capacitors instead erode their dielectric, with capacitance drops of 2–10 % per 10 000 hours [Montanari, 2011].

- Supplier strategies: thicker foils, larger cans, segmented electrodes. These increase size, weight, and cost but extend baseline life.

- Design strategies: derating voltage by 1.5×, paralleling devices for redundancy, or active monitoring of ESR.

Failure modes: capacitance loss, heating, dielectric breakdown.

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/fc/56/fc560a734e228ae9f5466272c5566b17/0124012165v2.jpeg)

COOLING SOLUTIONS

Maximize Lifetime & Power Density in High Power Semiconductors Modules

4. Resistors

Resistors seem passive, but thin-film types drift by 0.05–0.2 % per 1000 hours at 125 °C [Pan, 2015]. Such small drifts matter in precision circuits.

- Supplier strategies: low-TCR alloys, protective coatings; slightly higher cost.

- Design strategies: voltage derating, stress-relief trimming, or foil resistors in precision roles.

Failure modes: drift outside tolerance or open circuit.

5. Connectors and interconnects

Electrical interconnects include solder joints, sintered die attaches, and pluggable connectors. All degrade through fatigue, oxidation, or intermetallic growth. Solder intermetallics grow 0.5–2 µm per year [Huang, 2004], raising brittleness. Connectors show contact resistance increases of 50–200 % from fretting [Antler, 1984].

- Supplier strategies: Ni/Au plating, barrier layers, sintered Ag. These improve robustness but require costlier processes.

- Design strategies: underfill, mechanical stress relief, redundant spring contacts — targeted at the system stress profile.

Failure modes: intermittent contacts, heating, or catastrophic opens.

6. Cables

Cables combine metal conductors with polymer insulation. The conductor is stable, but polymers degrade: XLPE elongation can drop >30 % in ~10 years at 90 °C [Densley, 1974].

Water treeing is the most critical mechanism in XLPE. Under moisture and AC fields, tiny water-filled voids grow into “trees,” reducing dielectric strength and eventually triggering PD.

- Supplier strategies: tree-retardant XLPE, special extrusion processes. More expensive but baseline robust.

- Design strategies: metallic moisture barriers, double jackets, specified for humid or outdoor use.

Failure modes: dielectric breakdown, partial discharge, embrittlement.

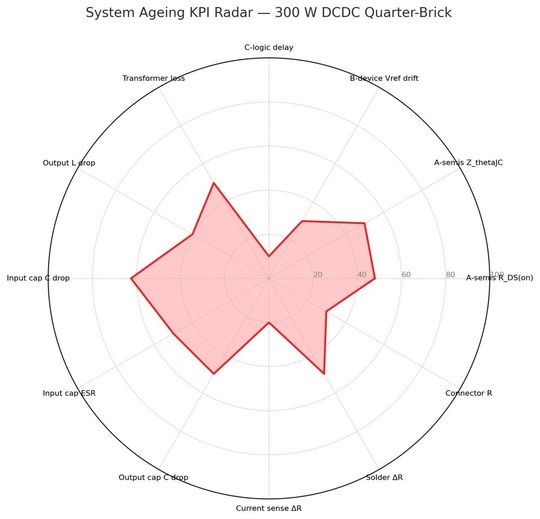

7. Entropy and normalised ageing KPIs

Because degradation is driven by irreversible entropy generation, it can be quantified by normalised KPIs — essentially how far each parameter has moved towards its datasheet end-of-life limit. Examples include ΔParam/SpecLimit, thermal impedance shift, or capacitance retention.Example — DCDC Quarter-Brick Snapshot

:quality(80):fill(efefef,0)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/60/c3/60c30b660b640/christian-schwabe-new-reliability-aspects-for-power-devices-in-application.jpeg)

Example — DCDC quarter-brick snapshot

Assume a 300 W quarter-brick running 25 000 hours (~3 years) at 55 °C inlet air and 80 % load. A KPI dashboard quantifies degradation:

| Subsystem | Parameter | Obs. change | EoL limit | KPI % tol. used | Status |

| A-semis | R_\text{DS(on)} | +12 % | +25 % | 48 % | 🟧 |

| A-semis | Z_{\theta\text{JC}} | +15 % | +30 % | 50 % | 🟧 |

| B-device | V_\text{ref} drift | +0.6 % | ±2 % | 30 % | 🟩 |

| C-logic | Delay | +1 % | +10 % | 10 % | 🟩 |

| Transformer | Core loss | +10 % | +20 % | 50 % | 🟧 |

| Output L | L drop | −6 % | −15 % | 40 % | 🟧 |

| Input cap | C drop | −25 % | −40 % | 62.5 % | 🟥 |

| Input cap | ESR | 3× | 6× | 50 % | 🟧 |

| Output cap | C drop | −10 % | −20 % | 50 % | 🟧 |

| Current sense | ΔR/R | +0.1 % | +0.5 % | 20 % | 🟩 |

| Solder | ΔR | +5 mΩ | +10 mΩ | 50 % | 🟧 |

| Connector | Contact-R | +30 % | +100 % | 30 % | 🟩 |

Interpretation:

- The critical bottleneck is the input electrolytic capacitor, already consuming >60 % of its allowable tolerance.

- Thermal resistance and transformer losses are around half-way to end-of-life, indicating steady but less urgent ageing.

- Logic and current-sense elements remain comfortably in the green zone.

- The aggregate picture is a system mid-life state: not immediately endangered, but one weak link (capacitor) will dictate service needs.

Radar plot showing KPI “shape,” dominated by input capacitor degradation

Conclusion

Every class of component in power electronics follows its own physics of degradation, but all are united by entropy generation. Suppliers extend baseline robustness through material and process innovations, while system designers leverage application knowledge to derate, oversize, or add redundancy. Together these measures balance cost and lifetime.

By quantifying degradation in normalised KPIs and visualising system health, engineers can anticipate failures, plan maintenance, and design next-generation systems with realistic lifetime expectations.

Abbreviations used

- NBTI/PBTI = (negative/positive) bias-temperature instability

- TDDB = time-dependent dielectric breakdown

- EM = electromigration

- R\text{DS(on)} = MOSFET on-resistance

- V\text{CE(sat)} = IGBT saturation voltage

- ΔT\text{j} = junction-temperature swing

- Z\theta\text{JC} = thermal impedance (junction-to-case)

- μ = permeability

- B_\text{sat} = saturation flux density

- ESR = equivalent series resistance

- tan δ = dissipation factor

- TCR = temperature coefficient of resistance

- IMC = intermetallic compound

- CTE = coefficient of thermal expansion

- XLPE = cross-linked polyethylene

- PD = partial discharge

- KPI = key performance indicator

- RUL = remaining useful life

- E_a = activation energy

References

- Antler, M., 1984. Fretting corrosion in electrical connectors. IEEE Trans. Components, Hybrids, and Manufacturing Technology, 7(1), 64–75.

- Bauer, P., 2015. Entropy generation as a measure of degradation. Journal of Applied Physics, 118(15), 154902.

- Black, J.R., 1969. Electromigration—A brief survey and some recent results. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, 16(4), 338–347.

- Ciappa, M., 2002. Selected failure mechanisms of modern power modules. Microelectronics Reliability, 42(4–5), 653–667.

- Densley, J., 1974. Ageing mechanisms and diagnostics for power cables. IEEE Trans. Electrical Insulation, EI-9(4), 199–210.

- Engelmaier, W., 1983. Fatigue life of leadless chip carrier solder joints during power cycling. IEEE Trans. Components, Hybrids, and Manufacturing Technology, 6(3), 232–237.

- Herzer, G., 2013. Modern soft magnets: Amorphous and nanocrystalline materials. Acta Materialia, 61(3), 718–734.

- Huang, M.L., 2004. Intermetallic compound formation in lead-free solder joints. Journal of Electronic Materials, 33(12), 1452–1458.

- Hu, C., 1992. Hot-electron reliability of MOS VLSI circuits. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, 32(2), 375–385.

- IEC, 2013. IEC 60216 — Electrical insulating materials — Thermal endurance properties. International Electrotechnical Commission.

- Ielmini, D., 2011. Modeling the universal set/reset characteristics of bipolar RRAM by field- and temperature-driven filament growth. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, 58(12), 4309–4317.

- Kaczer, B., 2005. Impact of NBTI on transistor performance and scaling. Microelectronics Reliability, 45(1), 39–46.

- Kondekar, P., 2021. Degradation of semiconductor devices under bias stress. Journal of Semiconductor Technology and Science, 21(5), 373–385.

- Montanari, G.C., 2011. Aging phenomena in metallized film capacitors under DC and AC stress. IEEE Trans. Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation, 18(5), 1471–1479.

- Pan, R., 2015. Aging effects in precision resistors. IEEE Trans. Device and Materials Reliability, 15(4), 580–587.

- Saha, D., 2006. Effect of oxide traps on CMOS analog circuits. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, 53(5), 1103–1111.

- Schroder, D.K., 2002. Semiconductor Material and Device Characterization. 3rd ed., Wiley-IEEE.

- Shokrollahi, H., 2017. Magnetic properties and microstructure of ferrite materials. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 423, 69–82.

- Smet, V., 2011. Aging and failure modes of IGBT modules in high-temperature power cycling. IEEE Trans. Industrial Electronics, 58(10), 4931–4941.

- Venkat, N., 2002. Reliability of aluminum electrolytic capacitors. IEEE Trans. Components and Packaging Technologies, 25(1), 154–162.

- Zhang, Z., 2014. Die-attach and substrate technologies for high-temperature power electronics. IEEE Trans. Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology, 4(12), 1942–1951.

(ID:50629511)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/f5/d2/f5d2bce7c01775fe62d4c6ecebc8c5ba/0129188745v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/38/cb38bf951c0af8a8de423fedce2489d8/0129352475v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b8/13/b8139abf82c98aa04248a4a119d28c13/0129194616v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/62/80/6280da00d591873bf8f0b2a70e5986e0/0129064771v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/60/40/6040b2e00aef20b4f9d92e8ac9f79c32/0129349725v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b3/13/b313941dbf7adc57c6d144966106d82b/0129219607v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/56/a4/56a4d9b6ee131a7a00b8b89dabf108f9/0128979281v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/67/62/676279913d77e1db48eb5cbe9be4c767/0128937895v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/f0/d8/f0d82f06ed1b7abb3245dfc4c317cb55/0127949994v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/6e/e5/6ee5ad1dc45fd69a5a5718147605850a/0129347492v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/7d/40/7d406bd959b3a9127c33a66157f9030a/0128339184v4.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/65/22/65223bc58811ced76adbfa7b5615d532/0129061536v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/23/ee/23ee4a97790d6009dbfd7d9577ffa723/0129220424v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/3c/d1/3cd1cacbceb792ba63727199c61ca434/0127801860v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/5a/a0/5aa0436498af618297961fd54ab36cdf/0126290792v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/cb/30/cb30ebdca7fcaea281749cb396654eb3/0124716339v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/thumbor.vogel.de/f3g2ouosszYDI6Qcyea5EqIzON0=/500x500/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/68/83/6883a88b8c321/ole-gerkensmeyer.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/5f/71/5f71d5f92a5f6/2000px-rogers-corporation-logo-svg.png)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/68/2c/682c3e2e9a195/logotype-rvb.jpeg)

:fill(fff,0)/p7i.vogel.de/companies/68/08/6808a2b3b6595/het-logo.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/b1/0a/b10a283cdf3e5f156781a7273c71a7e0/0129107484v2.jpeg)

:quality(80)/p7i.vogel.de/wcms/ea/f4/eaf4ed9f8eed646233fb8b45d66f8c9d/0126167501v2.jpeg)